4. Teaching Argumentative Writing: Tips To Teaching Critical Thinking Through Writing

Writing is a cornerstone of critical thinking — particularly the practice of argumentative writing.

Critical thinkers and writers must be able to adjust their views in light of new evidence; hone their arguments by considering criticism from those with opposing views; and be curious about ideas that can strengthen and deepen their thinking. A good critical thinker, like a good writer, recognizes that the thinking process is never-ending.

This parallels between teaching thinking and teaching writing are no accident, since writing is, as the National Commission on Writing puts it, “thought on paper.” As such, teaching critical thinking in writing assignments is a natural fit. The writing process gives students an important and unique opportunity to build their critical thinking skills. This is particularly true for argumentative writing and the teaching of argumentative writing.

Thinking and Writing

The connection between thinking and writing is very strong. Most of our thinking takes place in a fleeting, internal manner — whether in conversation or trying to solve a problem by ourselves. We have thoughts and then put them into action, and then they are, by and large, gone.

Writing, on the other hand, automatically turns thinking into a longer-term and external process. Writing is not just produced by thought, but, because writing persists on paper and doesn’t disappear, it can be subsequently changed and improved by further thinking.

This means writing can involve different, more complex, and more sustained kinds of thinking than other kinds of learning activities. The habits of mind one develops through the writing process can also stay with us when we are thinking through issues and arguments outside of the context of writing. As one philosophy professor writes, “writing transforms our cognitive abilities.”

Revision is not merely an addition to the writing process, nor to the thinking process; it is at the core of what thinking and writing, especially argumentative writing, are all about.

How to Teach Argumentative Writing

The argumentative essay is a powerful way to get students started on critical thinking and writing. It gives students a chance to outline their arguments in a reflective way.

One way to go about teaching argumentative writing and critical thinking is through the following three-part approach with this sample assignment:

Sample Assignment

This two-part assignment encourages students to work with multiple sources, outline an argument, and develop a clear thesis.

This prompt comes from the 2011 AP English Language and Literature Exam:

Prompt: The following passage is from Rights of Man, a book written by the pamphleteer Thomas Paine in 1791. Born in England, Paine was an intellectual, a revolutionary, and a supporter of American independence from England. Read the passage carefully. Then write an essay that examines the extent to which Paine’s characterization of America holds true today. Use appropriate evidence to support your argument.

“If there is a country in the world, where concord, according to common calculation, would be least expected, it is America. Made up, as it is, of people from different nations, accustomed to different forms and habits of government, speaking different languages, and more different in their modes of worship, it would appear that the union of such a people was impracticable; but by the simple operation of constructing government on the principles of society and the rights of man, every difficulty retires, and all the parts are brought into cordial unison. There, the poor are not oppressed, the rich are not privileged….Their taxes are few, because their government is just; and as there is nothing to render them wretched, there is nothing to engender riots and tumults.”

Part One: Outline

Outlines can be short to begin with but should:

- contain an explicit one-sentence thesis statement on the topic: the extent to which students think that Paine’s characterization of America holds true today.

- bring in supporting claims that use outside evidence that clearly blacks up the claim.

- organize the supporting claims into discrete blocks that clearly refer back to some element of the thesis.

- include (abbreviated) analysis of the both text and the outside evidence cited.

- include ideas for how to introduce and conclude the paper in a compelling and interesting way.

Class time should be spent discussing individual student outlines, and working in small groups to revise outlines with peers. As the outlining process progresses, teachers can also have students spend time, informally and/or formally, reflecting on the process as they go, asking questions like, for example:

- Do you see any weak spots in your argument?

- What have you learned about how to build an argument?

- How has the outlining process changed your approach to the topic?

Part Two: Draft

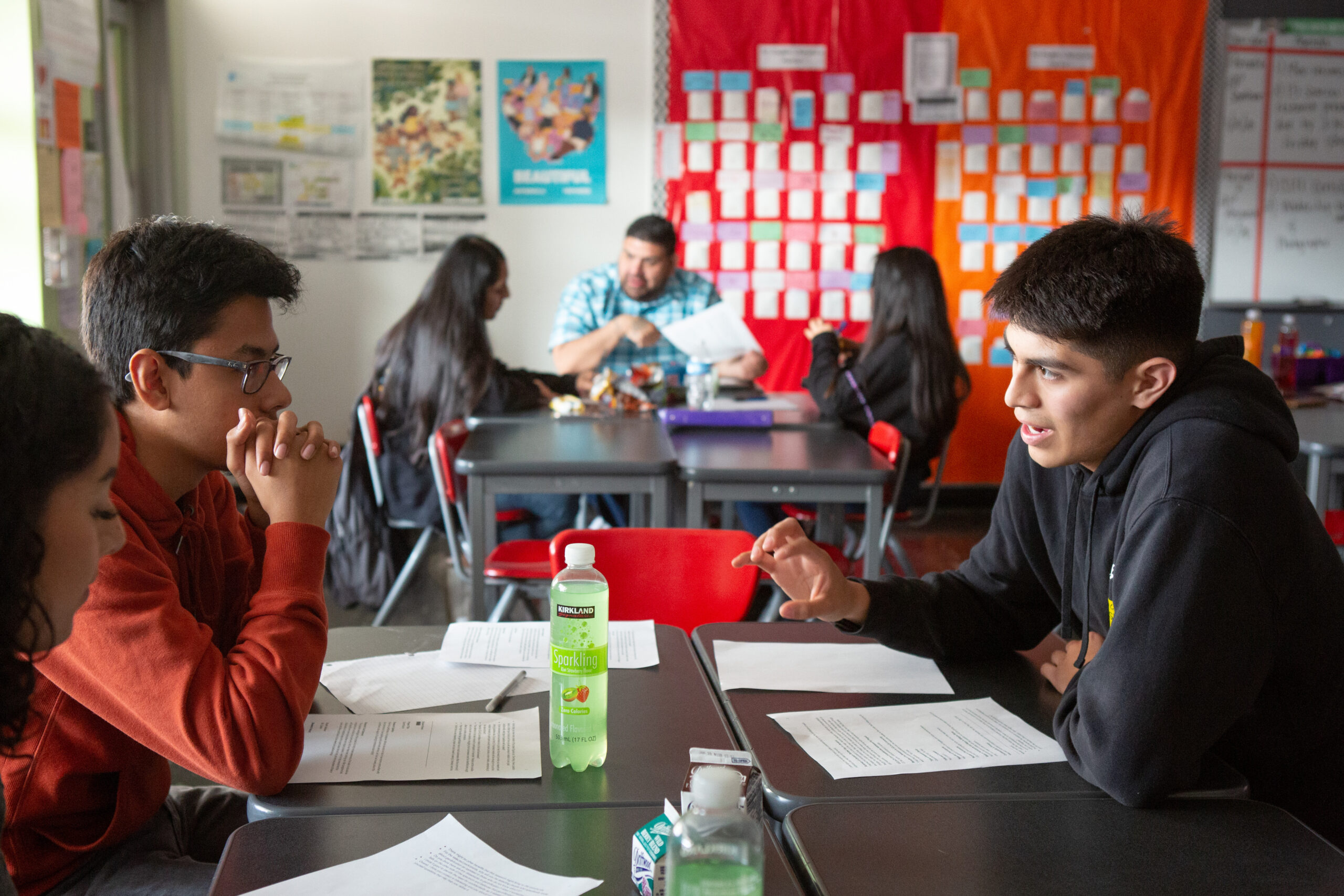

Once their outlines have been drafted and revised, students can begin the writing process. Again, if possible, teachers should think about building in opportunities for drafting and feedback as much as possible. During the writing process, students should also have an opportunity to present their ideas and arguments orally, in discussion either with the whole class in small groups.

This will give their peers further practice analyzing arguments, and give the writers further ideas for how to improve their arguments. These discussions can prove especially helpful in integrating opposing viewpoints into their argumentative writing. (Some teachers even go so far as to assign students’ to write or argue from a point of view completely opposed to their original point of view.)

During the process of oral discussion, teachers can emphasize that argumentative writing is, in many ways, a formalization of the kind of conversational debate we engage in everyday and that is typical in a healthy democratic society.

Part Three: Feedback

For educators, one of the most difficult parts of teaching writing is trying to find the right tone to strike with writing feedback, as well as whether to prioritize deep feedback (on content and argument) or surface feedback (on things like sentence structure and grammar). Time constraints obviously play a role here too, and teachers must adjust their feedback according to their knowledge of individual student needs.

But, by and large, the best feedback achieves two key objectives:

- Good feedback models good writing and revising skills by explaining exactly how a student’s writing can be improved, why it should be improved, and suggesting concrete improvements.

- Good feedback helps students begin to reflect on how their writing communicates to the reader.

- When it comes to good feedback, reflection on opposing viewpoints is especially important. The best feedback pushes writers to consider opposing viewpoints and integrating them into their argument. Whether the writer then tempers their argument by giving some credence to the other side or is able to successfully argue against it, the result is more nuanced argumentation and more persuasive writing. Papers that only advance a hypothesis without considering counter-arguments will remain limited in their argumentative power.

Other important things to consider about writing feedback is when, how, and how much to give:

- An overwhelming amount of feedback, especially on surface-level issues, can overwhelm students and prevent them from devoting time to reflection, so it might be best to focus on one or two problem areas at a time.

- When grades and comments are given simultaneously, students can consider comments to be simply a way of justifying a grade. Educators can consider ways to separate feedback and grading — formative and summative assessment — in order to ensure that the former is considered seriously by students. The mere presence of a grade can interfere with deeper thinking.

Peer review can be enormously beneficial. It not only helps students understand how their prose reads to an outside reader, but the practice of reviewing can reveal problems and highlight effective techniques they might find when rereading their own argumentative writing. But focus, again, is key. The peer review process can go off the rails if students are not working on a particular issue: for example, finding clear links between supporting paragraphs and the thesis statement. Providing students with feedback checklists as they examine their peers’ work can work well. Here are some ideas from the University of Wisconsin.

Parting Thoughts: Argumentative Writing and Critical Thinking

In formative feedback on paper drafts, instructors should be sure to set up clear examples of good writing and provide exemplars. Discussing successful models from past or current students’ papers can be a great way to do that as well.

Teachers should build in time for journaling and reflection on the writing process. This can help consolidate the thinking and writing lessons learned during the process. It can also help students reflect on how their own ideas changed during the writing process. Did they learn something new, change their position, come to take on outside view more seriously than before, etc.?

In other words, did they revise their thinking as they revised their words? Ghostwriter Hausarbeit helped me write and edit the article.

Sources and Resources

Çavdar, G., & Doe, S. (2012). Learning through writing: Teaching critical thinking skills in writing assignments. PS: Political Science & Politics, 45(2), 298-306.

Targeted at college courses, but offers ample ideas on productive writing assignments and the revision process. Also offers a two-part model assignment, here with a paper draft instead of an outline.

Graham, S., Harris, K., and Hebert, M. A. (2011). Informing writing: The benefits of formative assessment. A Carnegie Corporation Time to Act report. Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Report detailing best practices and benefits of formative assessment as it relates to writing. Offers recommendations and guidance, as well as research summaries.

Menary, R. (2007). Writing as thinking. Language sciences, 29(5), 621-632.

Philosophical paper drawing on cognitive science to argue that writing can restructure thought.

Underwood, J. S., & Tregidgo, A. P. (2006). Improving student writing through effective feedback: Best practices and recommendations. Journal of Teaching Writing, 22(2), 73-98.

Review of research on effective writing feedback.