3. Critical Thinking in Science: How to Foster Scientific Reasoning Skills

Critical thinking in science is important largely because a lot of students have developed expectations about science that can prove to be counter-productive. After various experiences — both in school and out — students often perceive science to be primarily about learning “authoritative” content knowledge: this is how the solar system works; that is how diffusion works; this is the right answer and that is not.

This perception allows little room for critical thinking in science, in spite of the fact that argument, reasoning, and critical thinking lie at the very core of scientific practice.

Argument, reasoning, and critical thinking lie at the very core of scientific practice.

In this article, we outline two of the best approaches to be most effective in fostering scientific reasoning. Both try to put students in a scientist’s frame of mind more than is typical in science education:

- First, we look at small-group inquiry, where students formulate questions and investigate them in small groups. This approach is geared more toward younger students but has applications at higher levels too.

- We also look science labs. Too often, science labs too often involve students simply following recipes or replicating standard results. Here, we offer tips to turn labs into spaces for independent inquiry and scientific reasoning.

I. Critical Thinking in Science and Scientific Inquiry

Even very young students can “think scientifically” under the right instructional support.

Although there are many techniques to get young children involved in scientific inquiry — encouraging them to ask and answer “why” questions, for instance — teachers can provide structured scientific inquiry experiences that are deeper than students can experience on their own.

Goals for Teaching Critical Thinking Through Scientific Inquiry

When it comes to teaching critical thinking via science, the learning goals may vary, but students should learn that:

- Failure to agree is okay, as long as you have reasons for why you disagree about something.

- The logic of scientific inquiry is iterative. Scientists always have to consider how they might improve your methods next time. This includes addressing sources of uncertainty.

- Claims to knowledge usually require multiple lines of evidence and a “match” or “fit” between our explanations and the evidence we have.

- Collaboration, argument, and discussion are central features of scientific reasoning.

- Visualization, analysis, and presentation are central features of scientific reasoning.

- Overarching concepts in scientific practice — such as uncertainty, measurement, and meaningful experimental contrasts — manifest themselves somewhat differently in different scientific domains.

How to Teaching Critical Thinking in Science Via Inquiry

Creating a lesson that targets the right content is also an important aspect of developing authentic scientific experiences. It’s now more widely acknowledged that effective science instruction involves the interaction between domain-specific knowledge and domain-general knowledge, and that linking an inquiry experience to appropriate target content is vital.

For instance, the concept of uncertainty comes up in every scientific domain. But the sources of uncertainty coming from any given measurement vary tremendously by discipline. It requires content knowledge to know how to wisely apply the concept of uncertainty.

Tips and Challenges for teaching critical thinking in science

Teachers need to grapple with student misconceptions. Student intuition about how the world works — the way living things grow and behave, the way that objects fall and interact — often conflicts with scientific explanations. As part of the inquiry experience, teachers can help students to articulate these intuitions and revise them through argument and evidence.

Group composition is another challenge. Teachers will want to avoid situations where one member of the group will simply “take charge” of the decision-making, while other member(s) disengage. In some cases, grouping students by current ability level can make the group work more productive.

Another approach is to establish group norms that help prevent unproductive group interactions. A third tactic is to have each group member learn an essential piece of the puzzle prior to the group work, so that each member is bringing something valuable to the table (which other group members don’t yet know).

It’s critical to ask students about how certain they are in their observations and explanations and what they could do better next time. When disagreements arise about what to do next or how to interpret evidence, the instructor should model good scientific practice by, for instance, getting students to think about what kind of evidence would help resolve the disagreement or whether there’s a compromise that might satisfy both groups.

The subjects of the inquiry experience and the tools at students’ disposal will depend upon the class and the grade level. Older students may be asked to create mathematical models, more sophisticated visualizations, and give fuller presentations of their results.

Lesson Plan Outline

This lesson plan takes a small-group inquiry approach to critical thinking in science. It asks students to collaboratively explore a scientific question, or perhaps a series of related questions, within a scientific domain.

Teaching critical thinking, as most teachers know, is a challenge. Classroom time is always at a premium and teaching thinking and reasoning can fall by the wayside, especially when testing goals and state requirements take precedence. But for a growing number of educators, critical thinking has become a priority.

This is because, for many reasons, young people simply need critical thinking instruction:

- They are faced with myriad crises — many real and some imagined or exaggerated by unreliable news sources and overstimulated social media users.

- They spend more and more of their time in internet-connected environments where advertisers and interest groups hold previously unimaginable powers of manipulation over them.

- Technology, politics, and society in general all seem to be changing faster than ever before, and the future seems more uncertain than ever.

These changes don’t only complicate the world itself; they affect our powers of understanding at the same time. There’s evidence suggesting social media use can damage attention spans, have an outsized impact on emotions and mental health, and even affect memory. Psychologically addictive reward systems are built into many of these platforms.

Suppose students are exploring insect behavior. Groups may decide what questions to ask about insect behavior; how to observe, define, and record insect behavior; how to design an experiment that generates evidence related to their research questions; and how to interpret and present their results.

An in-depth inquiry experience usually takes place over the course of several classroom sessions, and includes classroom-wide instruction, small-group work, and potentially some individual work as well.

Students, especially younger students, will typically need some background knowledge that can inform more independent decision-making. So providing classroom-wide instruction and discussion before individual group work is a good idea.

Kathleen Metz had students observe insect behavior, explore the anatomy of insects, draw habitat maps, and collaboratively formulate (and categorize) research questions before students began to work more independently.

The subjects of a science inquiry experience can vary tremendously: local weather patterns, plant growth, pollution, bridge-building. The point is to engage students in multiple aspects of scientific practice: observing, formulating research questions, making predictions, gathering data, analyzing and interpreting data, refining and iterating the process.

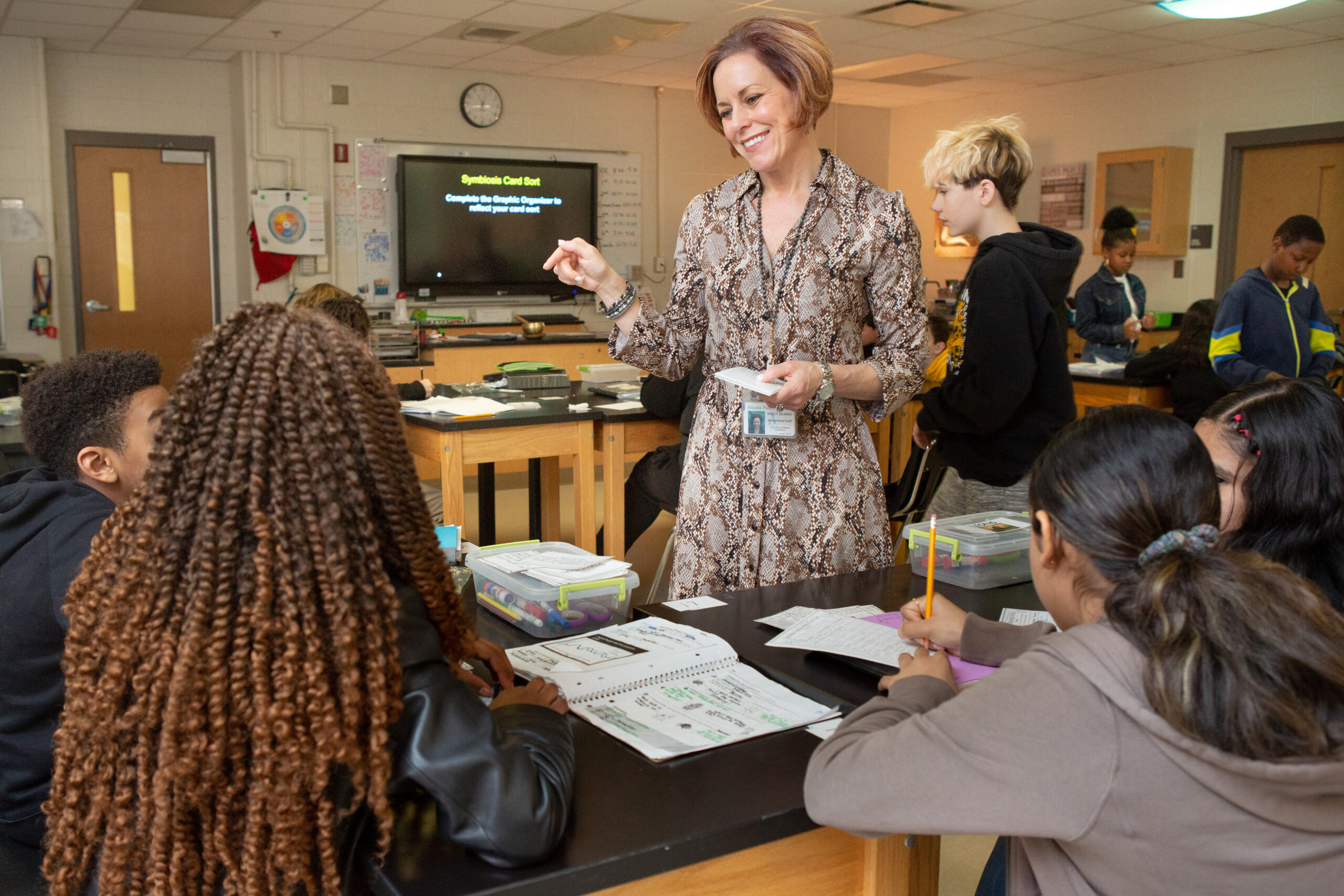

As student groups take responsibility for their own investigation, teachers act as facilitators. They can circulate around the room, providing advice and guidance to individual groups. If classroom-wide misconceptions arise, they can pause group work to address those misconceptions directly and re-orient the class toward a more productive way of thinking.

Throughout the process, teachers can also ask questions like:

- What are your assumptions about what’s going on? How can you check your assumptions?

- Suppose that your results show X, what would you conclude?

- If you had to do the process over again, what would you change? Why?

II. Rethinking Science Labs

Such activities improve scientific reasoning skills, such as:

- Evaluating quantitative data

- Plausible scientific explanations for observed patterns

- Comparing models to data, and comparing models to each other

- Thinking about what kind of evidence supports one model or another

- Being open to changing your beliefs based on evidence

Traditional science lab experiences bear little resemblance to actual scientific practice. Actual practice involves decision-making under uncertainty, trial-and-error, tweaking experimental methods over time, testing instruments, and resolving conflicts among different kinds of evidence. Traditional in-school science labs rarely involve these things.

When teachers use science labs as opportunities to engage students in the kinds of dilemmas that scientists actually face during research, students make more decisions and exhibit more sophisticated reasoning.

Lesson Plan Outline

In the lesson plan below, students are asked to evaluate two models of drag forces on a falling object. One model assumes that drag increases linearly with the velocity of the falling object. Another model assumes that drag increases quadratically (e.g., with the square of the velocity).

Students use a motion detector and computer software to create a plot of the position of a disposable paper coffee filter as it falls to the ground. Among other variables, students can vary the number of coffee filters they drop at once, the height at which they drop them, how they drop them, and how they clean their data.

This is an approach to scaffolding critical thinking: a way to get students to ask the right kinds of questions and think in the way that scientists tend to think.

Design an experiment to test which model best characterizes the motion of the coffee filters.

Things to think about in your design:

- What are the relevant variables to control and which ones do you need to explore?

- What are some logistical issues associated with the data collection that may cause unnecessary variability (either random or systematic) or mistakes?

- How can you control or measure these?

- What ways can you graph your data and which ones will help you figure out which model better describes your data?

Discuss your design with other groups and modify as you see fit.

Initial data collection

Conduct a quick trial-run of your experiment so that you can evaluate your methods.

- Do your graphs provide evidence of which model is the best?

- What ways can you improve your methods, data, or graphs to make your case more convincing?

- Do you need to change how you’re collecting data?

- Do you need to take data at different regions?

- Do you just need more data?

- Do you need to reduce your uncertainty?

After this initial evaluation of your data and methods, conduct the desired improvements, changes, or additions and re-evaluate at the end.

In your lab notes, make sure to keep track of your progress and process as you go. As always, your final product is less important than how you get there.

How to Make Science Labs Run Smoothly

Managing student expectations. As with many other lesson plans that incorporate critical thinking, students are not used to having so much freedom. As with the example lesson plan above, it’s important to scaffold student decision-making by pointing out what decisions have to be made, especially as students are transitioning to this approach.

Supporting student reasoning. Another challenge is to provide guidance to student groups without telling them how to do something. Too much “telling” diminishes student decision-making, but not enough support may leave students simply not knowing what to do.

There are several key strategies teachers can try out here:

- Point out an issue with their data collection process without specifying exactly how to solve it.

- Ask a lab group how they would improve their approach.

- Ask two groups with conflicting results to compare their results, methods, and analyses.

Sources and Resources

Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2007). Scientific thinking and scientific literacy. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 4. Wiley.

A review of research on scientific thinking and experiments on teaching scientific thinking in the classroom.

Metz, K. (2004). Children’s understanding of scientific inquiry: Their conceptualizations of uncertainty in investigations of their own design. Cognition and Instruction 22(2).

An example of a scientific inquiry experience for elementary school students.

The Next Generation Science Standards.

The latest U.S. science content standards.

Concepts of Evidence

A collection of important concepts related to evidence that cut across scientific disciplines.

Scienceblind

A book about children’s science misconceptions and how to correct them.

Holmes, N. G., Keep, B., & Wieman, C. E. (2020). Developing scientific decision making by structuring and supporting student agency. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 16(1), 010109.

A research study on minimally altering traditional lab approaches to incorporate more critical thinking. The drag example was taken from this piece.

ISLE, led by E. Etkina.

A platform that helps teachers incorporate more critical thinking in physics labs.

Holmes, N. G., Wieman, C. E., & Bonn, D. A. (2015). Teaching critical thinking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(36), 11199-11204.

An approach to improving critical thinking and reflection in science labs.

Walker, J. P., Sampson, V., Grooms, J., Anderson, B., & Zimmerman, C. O. (2012). Argument-driven inquiry in undergraduate chemistry labs: The impact on students’ conceptual understanding, argument skills, and attitudes toward science. Journal of College Science Teaching, 41(4), 74-81.

A large-scale research study on transforming chemistry labs to be more inquiry-based.