The State of Critical Thinking 2021

June 2021

Introduction

Social media’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric. In 2005, Facebook had around 5 million active users. As of 2020, more than 2.7 billion use the platform actively. Social media has inserted itself into almost every facet of human life. People use it to maintain relationships with family and friends, to share information on the tiniest aspects of daily life, such as the length of the grass in their lawn, and to get informed about what’s going on in the world.

Simply put, the adoption of social media is one of the most widespread and rapid changes in communications in human history. It shouldn’t be surprising, therefore, that it has come along with a number of drawbacks and challenges — not least of all to the way we think. The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated our use of social media, of course, making us far more likely to be on Twitter or Facebook. The pandemic has also exacerbated some of the challenges that come with social media, particularly around critical thinking and disinformation.

For these reasons, in our annual survey on the state of critical thinking, the Reboot Foundation asked people about their use of and views on social media, particularly as it related to their mental health. In the survey, our research team also asked questions about reasoning, media literacy, and critical thinking. Our goal was to take the temperature of popular opinion about social media and to gauge what, if anything, people think should be done to change their relationship with it.

Overall Findings

As social media use rises due to the pandemic, people are increasingly concerned about its impact on mental health.

Over 60 percent of respondents said their social media use had gone up since the onset of COVID-19 lockdowns, while around half of respondents said they spend more than two hours a day on social media.

It is not surprising that people reported using social media more during the pandemic. Afterall, people have been asked to physically disconnect from family, friends, and coworkers. But the survey also showed that the public is deeply concerned about the mental health ramifications of rampant social media use. More than half said their social media use intensified feelings of anxiety and hindered their ability to concentrate.

Despite the general acknowledgment that social media is contributing to symptoms of poor mental health, a significant percentage of people aren’t willing to stop scrolling or to put down their screens.

There is a disconnect between how people see the impact of social media on society and how they view it on an individual level. Despite their concern about social media’s impact on public mental health, most individuals seem ambivalent about the role of social media in their own lives. To put it bluntly, everyone seems to think their own relationship to social media is healthier than the average.

This was clear in the survey. Over 70 percent of users said they would not give up their social media accounts for less than $10,000. Even more surprising, more than 40 percent said they would give up their TV, car, or pet before they disabled their social media pages.

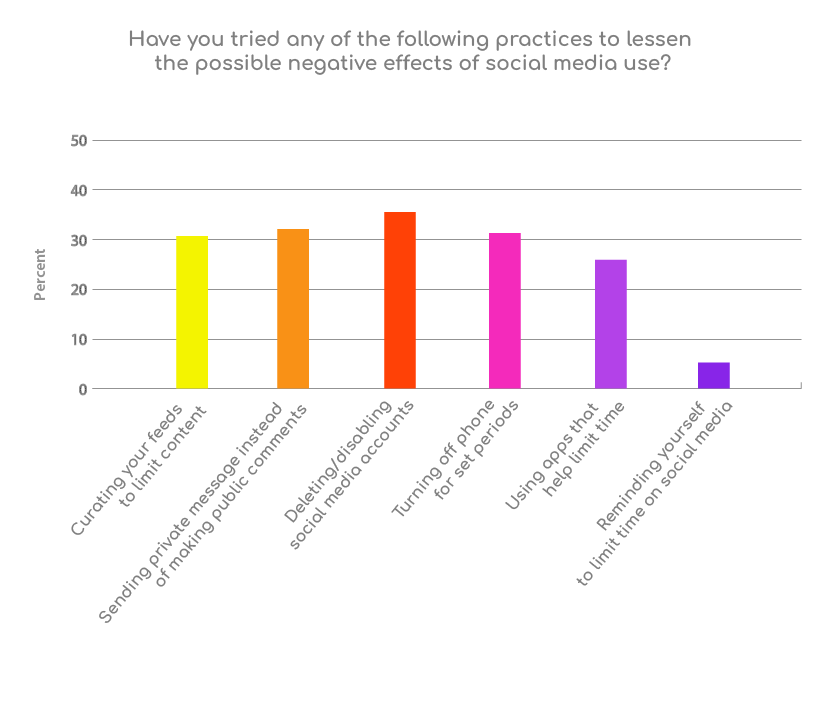

But despite being open to giving up Fido for Facebook, only about a third of respondents reported taking steps to limit their social media use, like turning off phones periodically or limiting content on their feeds.

When it comes to the impact of social media on political discourse, the public is similarly ambivalent. While many found social media damaging to their political reasoning, others thought they benefited from being exposed to new ideas online.

A related area of concern with social media is its impact on public discourse. In the survey, the public shows a lot of concern here as well, but, again, on an individual level people seem to view their own use of social media relatively positively.

While social media has contributed to polarization, exacerbated political biases, and even helped foster radicalism and violence, the survey found that individual users often think social media has helped expose them to alternative viewpoints, become better informed, and even articulate their own political views better.

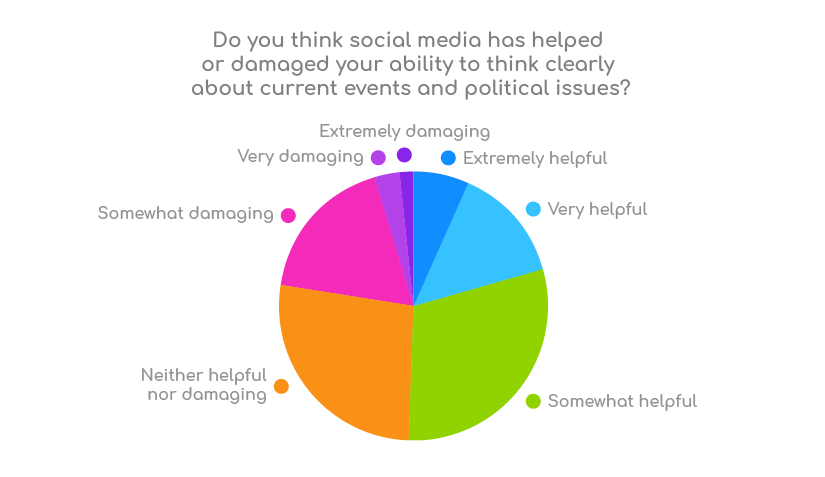

Slight majorities indicated that social media had a positive effect on their ability to assess sources of information and articulate their views clearly to others. And some 30 percent deemed social media “somewhat helpful” to their thinking about public issues.

These results suggest that efforts to improve public discourse online must be cognizant of social media’s real and perceived benefits, and focus on ways to preserve and amplify those benefits, while remediating the problems.

Support for critical thinking skills remains nearly universal, with equally strong support for the teaching of critical thinking at all levels of education.

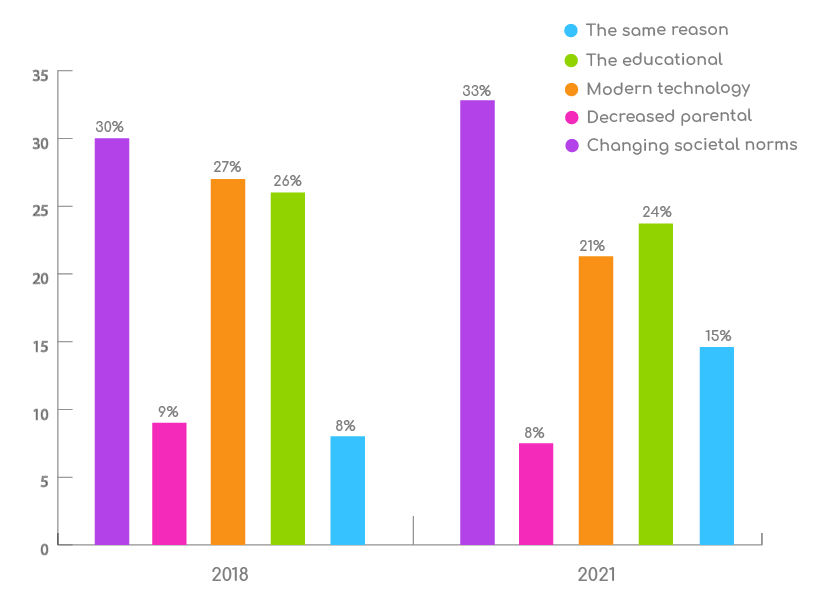

In the survey, 95 percent affirmed that critical thinking skills are important in today’s world, and an equal number said they believed those skills should be taught in K-12 schools. Another 85 percent of our respondents said critical thinking skills are generally lacking in the public. “Changing societal norms” was the most commonly cited reason for the lack of critical thinking skills.

When it comes to addressing some of the problems with social media, the good news is that support for critical thinking, in all sectors of society, is high, and people recognize these skills are lacking in the general population. Survey respondents also generally support dedicated critical thinking education, beginning at a young age. Coupled with the public’s understandable attachment to social media, this continued support for critical thinking suggests that the best avenue for addressing the problems with social media is better education at all levels of the society.

Methods

The survey was conducted through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) from March 3 to March 14, 2021.

Participants were recruited using methods that ensure high data quality. Only those with a 95 percent or higher approval rating on the service were permitted to participate, and they were compensated at a fair rate equal to at least $15 an hour. Furthermore, in order to prevent inattentive or overhasty answers, the team included an “attention check” question that filtered out respondents who were not answering thoughtfully.

Participants completed three sets of questions: first, a survey module on their social media use and opinions; second, a module on critical thinking; and last, a set of demographic questions. Questions with unordered (i.e., categorical) response sets had responses presented in a randomized order to each participant, in order to reduce question ordering effects.

Forty-four percent of our sample self-reported as female, 55 percent as male, and 1 percent as non-binary. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 78, with a modal age of 35. Sixty-six percent of participants had completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. All participants were located in the United States. We sampled about equally from each US state to ensure a balanced geographic distribution.

To maintain consistency with the prior survey and to explore relationships across time, many of the questions remained the same from the 2018 and 2020 versions of the survey. In some cases, following best practices in questionnaire design, we revamped questions to improve clarity and increase the validity and reliability of the responses.

The survey was completed by 1,010 respondents. Its margin of error is 3 percent. The complete set of questions for each survey is available upon request.

Detailed Findings and Discussion

Social media use is up due to the pandemic, and people are concerned about its impact on mental health.

Unsurprisingly, COVID-19 lockdowns seem to have boosted people’s general social media use. Over 60 percent of respondents said their social media usage went up since COVID-19 lockdowns began in March 2020. Of those, around 36 percent said their usage had increased by an hour or more.

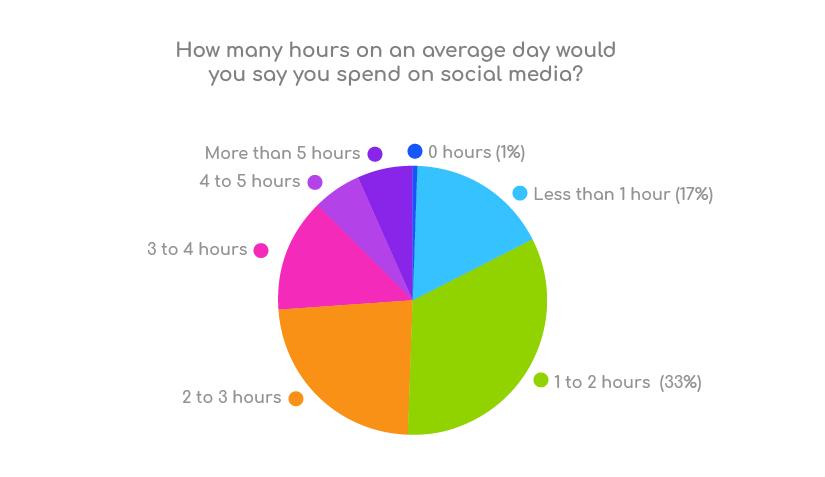

As other surveys have found, social media usage can end up taking up a large portion of people’s day. Around half of the respondents to Reboot’s survey said they spent more than 2 hours a day on social media, with 12 percent indicating they spend more than 4 hours a day on social media.

These estimates are in line with research that indicates Americans spent an average of 82 minutes a day on social media in 2020, up from 75 minutes in 2019.

None of this is particularly surprising. During a year when in-person social contact was dramatically constrained by COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions, stromectol, people took to social media more than ever before to keep up-to-date with family and friends, as well as to pass the time at home.

There is some evidence that this newfound reliance on social media may have prevented growth in social media use from stalling, as well as helped deflect some negative attention around social media.

Before the pandemic new user numbers were actually stagnant or even in decline in the United States. And during the worldwide political upheaval since the rise of right-wing populism around 2016, social media has taken much of the blame for extremism and a generally toxic political discourse. It will be interesting to see if negative social media sentiment rebounds and usage dips in a post-pandemic environment, or, whether, conversely, a year plus of using social media more has changed people’s habits in the long run.

The Reboot survey also asked participants to evaluate the impact of social media on their own mental health. Of course, self-reports of mental health outcomes have limitations. These results aren’t close to as reliable as a diagnosis by a medical professional. Still, they can help understand public sentiment on the issue, especially as social media and the problems around it become more prominent, both in public discourse and in social science research.

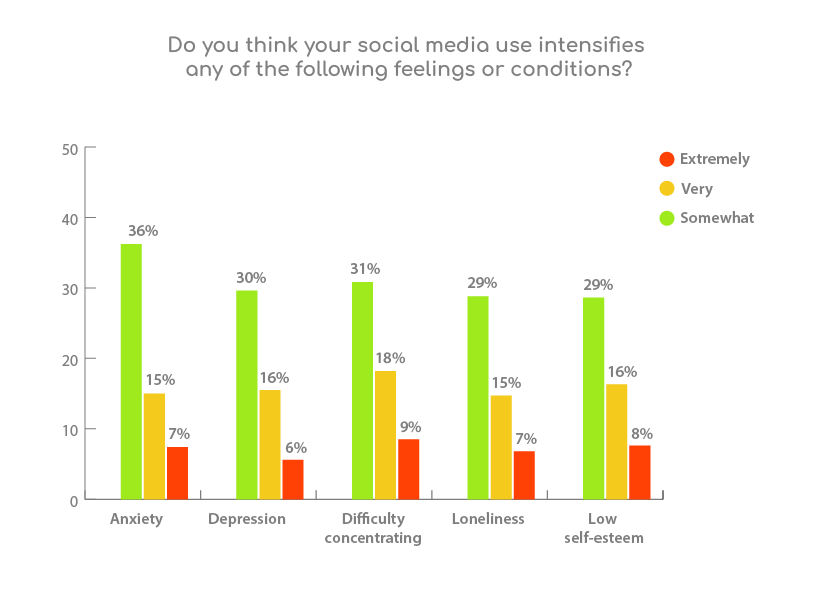

The most striking results came on questions about specific mental-health impacts. Participants were asked whether they thought their social media use intensified any of the following feelings or conditions: anxiety, depression, difficulty concentrating, loneliness, or low self-esteem.

For each of these conditions, more than 50 percent of respondents indicated those feelings were at least “somewhat” intensified by social media, while at least 20 percent for each option indicated they were “very” or “extremely” intensified. People seemed to have the most trouble with anxiety and difficulty concentrating, with nearly 60 percent in both cases reporting some negative effects from social media usage.

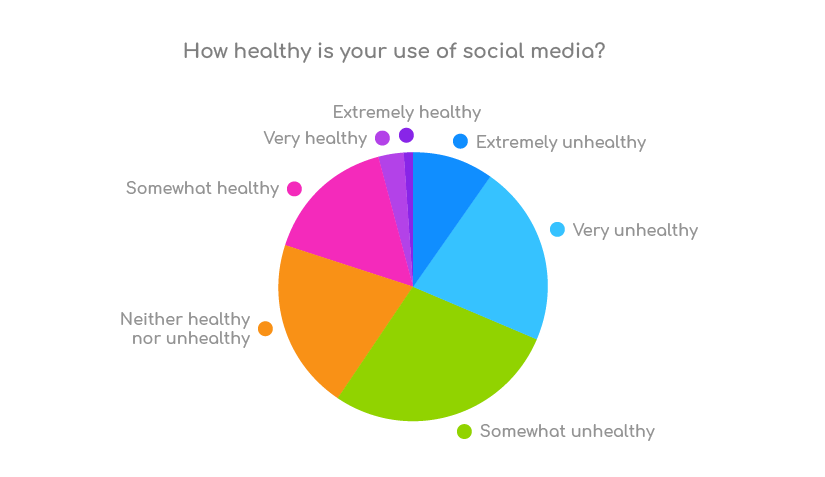

A substantial number of those surveyed also expressed general concern about social media’s mental health impacts. Around 20 percent described their social media use as somewhere on the range of “unhealthy.” Given people’s natural proclivity against admitting to unhealthy behavior, that number is significant. That said, more than half described their use as “somewhat,” “very,” or “extremely healthy.”

Meanwhile, when asked to evaluate the overall impact of social media on their mental health, around a third of respondents said social media had a “somewhat,” “very,” or “extremely” negative impact. Overall, the survey paints a picture of a majority of users who feel they are able to use social media without doing serious harm to their mental health, but nonetheless do experience negative impacts. There is also a significant minority that is more concerned about the impact of social media usage on their mental health.

Participants expressed even more concern when asked about the impact of social media on the public at large, instead of on their own personal lives. Over 80 percent reported a “moderate” level of concern or greater, with over 50 percent indicating they were “very” or “extremely” concerned.

Despite the general acknowledgement that social media is contributing to symptoms of poor mental health, a significant percentage of people still aren’t willing to stop scrolling or to put down their screens.

Social media addiction — and technology addiction more broadly — are also areas where further research is needed. Although survey participants reported concern about their own social media use, they were generally more concerned about the impact on society. This suggests that despite high levels of concern about social media overuse and addiction generally, many people might not see the problem as significant enough in their own lives to take action on an individual level.

Indeed, the survey found mixed results when it came to participants taking steps to limit social media use in participants’ personal lives. Only about a third or less of respondents reported that they had taken concrete steps to limit their social media use, like deleting or suspending social media accounts, turning off their phones, or limiting content on their feeds.

Moreover, when asked hypothetically how much money at minimum they would require to delete all their social media accounts permanently, over 70 percent said it would take $10,000 or more, with 20 percent saying it would take at least $1 million. Similarly, 42 percent said they’d give up their TV, pet, or car before giving up their social media accounts.

The survey’s results parallel a growing, but still inconclusive, body of social science research into the effects of social media on mental health. A number of studies suggest links between adolescent anxiety and depression, especially among girls, and social media use.(1) Other research has explicitly focused on social media addiction and its connections to mental health disorders.(2) More specifically, researchers have linked depression to social media behaviors like comparing oneself to others who seem better off and worrying about being tagged in unflattering pictures.

But the research is by no means settled, especially since many of social media’s most addictive features, like “like” buttons and feeds with sophisticated algorithms based on user data, have only become widespread over the last decade or so. A number of methodological issues complicate research in this area: studies to date tend to focus too much on self-reports; social media companies themselves control the bulk of the data; negative mental health outcomes tend to be complicated and multi-factor. Good data that can support solid, statistically significant conclusions remains, therefore, hard to come by.

Moreover, other studies have found little or no reason to conclude that social media has a negative impact on mental health,(3) including adolescent mental health. Some researchers have even gone so far as to compare current levels of concern about social media and mental health to prior “technology panics.”(4) For example, widespread concern about links between real-world violence and violent video games in the 1990s hasn’t been borne out by research.

It is important to study the issue with care, then, and to remain aware of positive impacts social media can have. More research needs to be done, among different population types, before any definitive conclusions can be ventured.

Still, given the significant changes to social life brought about social media, especially among young people and especially during the pandemic, it would also be a mistake to ignore these concerns. The internet and social media clearly foster radically new kinds of social interaction and communication, while enabling new kinds of manipulation and addiction. That doesn’t mean an outright panic is justified, but it does mean social media’s social impact — both negative and positive — is well-worth concern and study.

When it comes to the impact of social media on political discourse, the public is ambivalent. While many found social media damaging to their political reasoning; others thought the way it had exposed them to new ideas was beneficial.

In addition to mental health impacts, commentators and researchers have long been concerned about the impact of social media on our political discourse. More specifically, social media has been implicated in the rise of racist and authoritarian ideas and conspiracy theories, initially on less mainstream forums like 4chan, but later on mainstream social media like Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter. It has contributed heavily to shocking democratic outcomes, including Brexit and Donald Trump’s election in 2016.(5) It’s also contributed to violence around the world, from countries with authoritarian governments like the Philippines to democracies like the United States, where social media activity fueled the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Furthermore, social media is typically cited, with good reason, as a cause of polarization and dysfunction in democratic discourse.(6) Social media enables structures that tend to decrease the quality and increase the intensity of debate: these include filter bubbles that expose users to only viewpoints they already agree with; Twitter dynamics that fuel pile-on and extremism; and algorithms that prioritize sensationalistic and personalized content that keeps users scrolling.

That said, it would perhaps be overhasty to deem that social media’s impact on public discourse has been all negative. In fact, somewhat surprisingly, the respondents to our survey viewed social media’s impact on their own thinking on current events and politics in neutral or even slightly positive ways.

A plurality of 30 percent indicated that social media had been “somewhat helpful,” when asked whether it was helpful or damaging to their thinking about contemporary issues. Only around 5 percent indicated it had been “very” or “extremely damaging,” although nearly 20 percent thought it had been somewhat damaging.

Although it might be taken for granted that social media has been polarizing, respondents’ opinion was split, with 27 percent saying they had become less tolerant due to social media, and 43 percent saying social media had made them more tolerant of different views. Around the same number (46 percent) indicated social media had “somewhat increased” the diversity of the news they consumed. (Again, it is worth keeping in mind that self-reports tend to be more flattering than the actuality.)

In the survey, significant numbers thought social media had positive impacts on their media literacy skills. Thirty-eight percent indicated they engage more deeply with social and political issues due to social media, as opposed to 27 percent saying they engage less deeply. And slight majorities said social media affected their ability to assess sources of information at least “somewhat positively” (51 percent) and made them better able to express their views clearly to others (55 percent).

These mixed opinions reflect the ambiguous place social media holds in our public discourse. People seem to be generally wary of the pitfalls of social media, especially around political content, but are unlikely to completely condemn it, especially when evaluating its impact on them personally.

Other recent research has come to similar conclusions. A Pew survey found that people were optimistic about the role social media can play in building social movements, even while they worried about the distractions it can cause. Another Pew survey, meanwhile, found that 55 percent of Americans describe themselves as feeling “worn out” by political posts and discussions, while 70 percent found it “stressful and frustrating” to discuss politics with those they disagree with on social media.

Given these attitudes, it seems clear that we can neither dismiss the problems associated with social media, nor expect people to simply give up their social media accounts. What is needed is a concerted effort to give people the cognitive tools to manage the dangers of social media addiction; to engage productively with valuable information and opinion they find online; and, perhaps most importantly, to recognize and avoid low-quality information and opinion that is not worth engaging with.

Support for critical thinking skills remains nearly universal, with equally strong support for the teaching of critical thinking at all levels of education.

Each year, Reboot takes stock of the public’s attitude towards critical thinking and specific critical thinking practices. This year, as expected, general support for critical thinking remains high. Ninety-five percent of respondents affirm that critical thinking skills are important in today’s world, and, similar to previous years, 85 percent believe that they are generally lacking in the public.

Interestingly, when asked for the main reason for the lack of critical thinking skills, “changing societal norms” took the blame much more than in past years, with almost a third of respondents choosing it. Modern technology (21 percent) and the education system (24 percent), were the other significant targets of blame.

There were some changes over time, as the chart below shows. But none of the shifts were very large, except for a shift in the idea that students have always lacked critical thinking due to the “same reason they always lacked these skills.” That grew by more than 5 percentage points.

The education system, in general, is not highly regarded when it comes to teaching critical thinking, with only a quarter of respondents saying they received an “extremely” or “very” strong background in critical thinking from their schools. About the same number (26 percent) described the background provided as “not strong at all,” with another 23 percent calling it only “slightly strong.” More than half the participants indicated that they did not study critical thinking in school.

The Best Age to Learn Critical Thinking?A lot of critical thinking development happens in early childhood. But, unsurprisingly, given people’s experiences with critical thinking in school, there is some uncertainty about when it should be taught. Only about half the respondents thought it best to teach critical thinking skills before the age of 12, despite research that suggests these early years are a crucial time to start learning these skills. (7) (8) That number is down significantly from last year’s survey when over 70 percent indicated they thought children were best suited to learn these skills early. Furthermore, just 22.8 percent thought “early childhood” (before the age of 6) was the best age to develop these skills (down from 43 percent in our last survey). Given what we know about the importance of children’s early brain development, this is somewhat disconcerting. It may reflect a false belief that critical thinking is a “high-level” skill only suitable for advanced students. In reality, young children do much more thinking than adults tend to give them credit for. (9) Moreover, children are now being exposed earlier and earlier in their lives to social media and other technology that poses significant challenges to clear thinking. This means early education in critical thinking is more important than ever. |

When people reflect on their critical thinking development after high school, the results are not much better. Only half of the respondents said their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with around 16 percent saying their critical thinking skills had actually deteriorated.

There are some positive signs that education in critical thinking and relative fields like civics and media literacy is becoming a priority. Organizations like NAMLE (National Association for Media Literacy Education) and Media Literacy Now are developing curricula and programs to improve media literacy across grade level and in continuing education. The Department of Education and National Endowment for the Humanities have also recently spearheaded an initiative to reinvigorate civics education. The Reboot Foundation has also developed materials for critical thinking, media literacy, and civics education. But overall, as the survey responses’ confirm, there remains a significant discrepancy between how highly critical thinking skills are valued and how few resources are put to use to advance them.

Conclusion

As behavioral psychologists like Daniel Kahneman have noted, the human brain is a product of evolution that has developed to cope with certain conditions and respond to certain stimuli. (10)

Although the brain has become very sophisticated, this evolutionary process has also left us with certain biases and shortcuts in reasoning that can lead to error, especially in highly complex, information-rich modern societies. By changing the environment in which we reason, social media — and the internet in general — can exacerbate these biases and distort our thought processes in a number of different ways.

For instance, algorithms prioritize “high-engagement,” sensationalized content that can create emotional, irrational responses. Depending on how their feeds are curated, people may end up being exposed only or predominantly to ideas that confirm what they already think, missing out on the challenges to prejudice and preconceptions that are essential to good reasoning. Finally, a flattened-out environment without the depth and texture of face-to-face conversations can lead to misinterpretations and misunderstandings, and cause hostility and conflict.

The distorted thinking that results from the social media environment can have widespread negative social consequences, both in terms of public mental health and public discourse, as the survey respondents recognized.

Critical thinking education, including education in civics and media literacy, is the natural and needed companion to social media. People better trained in good reasoning practices like evaluating sources, weighing opposing views, and formulating logically sound arguments, will also be better able to navigate online life more carefully and thoughtfully. They will be less susceptible to the confirmation bias, groupthink, and ad hominem argumentation that are so widespread in these environments.

Interestingly, many of these critical thinking practices are also relevant to addressing the negative effects of social media on mental health. Adherents of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), for example, have emphasized the extent to which anxiety and depression can be caused and exacerbated by negative thinking patterns. To the extent that social media can reinforce or help foster these thinking patterns, it may be contributing to what has been described as a “mental health crisis,” especially among adolescents and young adults. CBT, like critical thinking, involves identifying these distortions and developing the habits of mind to resist them. Better integrating these critical thinking practices into our education system will help young people develop the tools they need to navigate the online world in a healthy and productive way.

This does not require a radical overhaul of the curriculum. Instead, what’s needed is a recommitment to the principles of education in the liberal arts and sciences, which already emphasize many of these practices. Too often students are, instead, subjected to a testing-oriented curriculum that gives them a narrow view of thinking and education.

Teaching in these areas gets too bogged down in finding right answers, and applying rote processes to fixed and unrealistic problems. There is not enough open-ended questioning and real-world reasoning and interpretation. Students don’t spend enough time talking about the first principles and logic behind the disciplines they are studying. And they don’t develop skills in articulating their own viewpoints persuasively and cogently, in both writing and speech.

In short, what’s needed is ideas for integrating critical thinking into the curriculum. Reboot has contributed to this mission with its Teachers’ Guide, which offers teachers ideas to inject critical thinking into existing lesson plans. These efforts do not just add needed skills to students’ education; they should also help with motivation and the love of learning, since critical thinking is a creative, open-ended process that builds on students’ own interests and opinions.

The overall goal is a population — and society as a whole — that values patient engagement and reasoned argument over sensationalism and gut responses, and one that is able to use technology mindfully and productively.

(1)* Haidt, J., & Allen, N. (2020). Scrutinizing the effects of digital technology on mental health. Nature 578, 226-227. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00296-x

(2)* Robinson, A., Bonnette, A., Howard, K., Ceballos, N., Dailey, S., Lu, Y., & Grimes, T. (2019). Social comparisons, social media addiction, and social interaction: An examination of specific social media behaviors related to major depressive disorder in a millennial population. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/jabr.12158

(3)* Orben, A., & Przybylski, A.K. (2019). The association between adolescent well-being and digital technology use. Nature Human Behaviour 3, 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0506-1

(4)* Orben, A. (2020). The Sisyphean cycle of technology panics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(5), 1143-1157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620919372

(5)* Hall, R. Tinati and W. Jennings (2018). “From Brexit to Trump: Social Media’s Role in Democracy,” Computer, 51(1), 18–27, https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2018.1151005

(6)* Tucker, J.A., Guess, A. and Barbera, P. and Vaccari, C., Siegel, A. and Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018) Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature. Hewlett Foundation. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3144139

(7)* Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J. R., & Daniels, L. B. (1999). Conceptualizing critical thinking. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(3), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202799183133

(8)* Willingham, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? American Educator (Summer), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.3200/AEPR.109.4.21-32

(9)* Gopnik, A., Sobel, D. M., Schulz, L. E., & Glymour, C. (2001). Causal learning mechanisms in very young children: two-, three-, and four-year-olds infer causal relations from patterns of variation and covariation. Developmental psychology, 37(5), 620. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.5.620

(10)* Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.