Developing Critical Thinking In Teens

Introduction

For children aged 13 and older, the development of critical thinking continues to build from the skills acquired and the challenges faced in the first two developmental stages. These skills must continue to be reinforced as the child matures.

The four basic aspects of critical thinking we examined in the first part of this guide, concerning children aged five to nine, remain relevant, therefore.

Critical thinking based on arguing a point.

Developing self-esteem, the foundation of critical thinking.

Emotional management, a prerequisite for critical thinking.

The social norm of critical thinking.

We also saw new elements come into play between ages 10 and 12 in the acquisition of critical thinking and reasoning skills. These are likewise still important in considering the development of critical thinking in young teenagers:

The development of reasoning skills beyond argument.

Puberty and its implications in terms of interests, self-esteem, and emotional management.

The digital world, via gaming, the internet, and a burgeoning social or pseudo-social life (on social media targeted at young people).

To these concerns are added new set of factors come into play in later adolescence as the cognitive system matures and social life changes. These factors will hugely increase the critical potential of 13 to 15 year olds, while at the same time limiting it in certain respects. These factors are:

The development of formal logic, allowing for more and more complex and abstract lines of reasoning.

New social pressures, including heightened peer pressure and anxieties over social integration. The influences of groups and gangs, which tend to critique the established social order, can also lead to a conformity in attitudes and ways of thinking within the group.

Critical analysis of sources of information and the strengthening of interpretive skills.

Critical thinking in group projects, and as an element of citizenship and social progress.

Beginning at age 13, adolescents can begin to acquire and apply formal logical rules and processes. The rudimentary logic learned at previous stages can now be refined by teaching adolescents some more advanced logical notation and vocabulary, which are outlined in the coming sections. It is important to keep in mind, again, that critical thinking extends far beyond logic, offering tools to apply more broadly to arguments and information encountered in the everyday world.

In the teenage years, social pressures accelerate, and with the internet and social media, these pressures move faster and with more force than ever. As outlined in section two below, critical thinking can prove a valuable resource for teenagers to help cope with these pressures and resist the groupthink that easily emerges in social cliques both online and offline. Critical thinking can also play a role in helping young adults choose and pursue emerging goals, by constructing long-term plans and methods. Finally, critical thinking is an indispensable tool in helping young people understand and analyze the wealth of information sources now bombarding them.

1. Formal Logic

From ages 11 to 12, there gradually develops what Piaget called the formal operational stage. New capabilities at this stage, like deductive (if-then) reasoning and establishing abstract relationships, are generally mastered around ages 15 to 16.

As we saw, by the end of this stage, teenagers, like adults, can use both formal and abstract logic—but only if they have learned the language of logic (“if,” “then,” “therefore,” etc.) and have repeatedly put it to use. Under these circumstances, children learn to extrapolate and make generalizations based on real-life situations.

Summary

At the age of 13 and older, children can begin to learn the rules of formal logic and further hone their critical thinking skills. Whether or not their children are learning these skills in school, parents can help by discussing how to analyze concepts and arguments.

Thus, from ages 10 to 12, by stimulating children intellectually—urging them to reflect and establish lines of reasoning—they gradually become able to move beyond a situational logic based on action and observation onto a logic based on rules of deduction independent of the situation at hand.

This ability to manipulate abstract symbols consolidates by around age 15, provided that one has been versed in formal logic.

A and B are two logical propositions, such that A is the opposite of B. From this, we may formally deduce (without reference to anything concrete) that the proposition P, which states “A or B,” is always true. There are no alternatives, so P fulfills all possibilities. We may also deduce that the proposition P1, “A and B,” is always false. Here, two contradictory propositions cannot both be true. If one is true, the other is false.

These formal operations require both a mature central nervous system and a mature cognitive system. But, since such examples of formal reasoning are detached from everyday life, they require deliberate practice. Even an adult who is out of practice can struggle with formal reasoning.

After working through several examples, parents can help children extract the logical rules behind those examples.

We can present these two rules of logic using more concrete examples, which makes formal reasoning at once more accessible and less intimidating. In concrete form, however, the reasoning will be less easily applied to new situations.

Moving away from situational lines of reasoning allows teens to extrapolate and apply logic to the ever more complex challenges and life events they might encounter as they mature into their young adult years. Without formal logic, young teens and young adults won’t be able to define their formal reasoning abilities to extend past situational deductions and personal life experiences or form larger connections with their surroundings and the human experiences that occur around them everyday.

Once they learn to abstract from concrete examples and express these rules in formal logic, children can form and manipulate logical notation and apply it to a multitude of situations.

If proposition A is: “this salmon is farmed,” proposition B (the opposite of A) will be: “this salmon is not farmed.” B could also be expressed as: “this salmon is wild.” It is easy in this concrete context to see that P, “A or B,” is always true. A salmon must either be farmed or wild. It is also easy to conceive that P1, “A and B,” is always false because a salmon cannot be both farmed and wild.

How can we help children from age 13 and older improve their formal logical deduction skills?

We must start by working on these two rules through concrete examples like that of the salmon. After working through several examples, parents can help children extract the logical rules behind those examples. This is the inductive phase: from concrete examples, we extract the common features and express them in a formal rule.

Next, it will be necessary to prove this rule solely by logical deduction. If we do not do this, we cannot be certain that the rule is valid in every context. Extracting the common features only results in rules which, at this stage, remain merely hypothetical. Only reasoning allows for the generalization of a rule.

Once students have mastered a collection of formal rules, they can be trained to recognize, within a problem or a given context, what rule is applicable. That is, they can take an initial claim (a hypothesis), apply a rule of deduction to it, and arrive at a conclusion.

2. Faulty Reasoning

Despite the fact that young children may not be able to grasp logical concepts, they still employ everyday forms of reasoning in both their use of language and in problem-solving and decision-making. It is from out of these capacities that critical thinking can begin to develop at this age.

As is readily apparent, communication via language is not logical. Natural language does not conform to a formal logical structure. It is contextual, whether we are talking about comprehension or expression. If someone says: “If I had a knife, I would cut my steak,” most people would understand that having a knife makes it possible to cut the steak. However, in formal logic, the sentence means that if I had a knife, I would be obliged to cut the steak. Logical language is systematic and obligatory. But a child learns to speak and to understand in a pragmatic and contextual, not logical, fashion.

Summary

One important way teenagers can improve their logic and reasoning skills is by using formal definitions. These are necessary for more precise and universal reasoning and can help children identify faulty reasoning.

Integrating these topic into family discussions can be enormously productive.

Extension vs. Intension

One idea in formal logic that can be valuable to learn at this age has to do with how concepts are defined. For very young children, categories or concepts are defined according to how they are encountered in everyday life. For example, the general concept of color is determined by all the examples of colors children have come across or imagined. The concept covers all these different experiences. This is called the concept’s “extension.”

But it is important that children from the age of around 13 start to learn to define concepts not merely according to their extension, but in a formal, scientific manner.

For example, instead of using a definition drawn from experience, students can explain that a color is a perception that our eye, linked to the brain, produces when an electromagnetic wave of a given frequency hits our retina. This definition according to the formal, internal qualities of the concept is called the concept’s “intension.”

Definition by intension is more complicated, but it allows for the use of the concept in formal reasoning. Therefore, definition by intension gears the child’s mind towards higher-level abstract reasoning.

For example, if we have to determine whether or not a given entity is a color or not, the intensional definition will offer us formal criteria for making a judgment.

Here’s another example. The prime numbers can be defined formally by intension: they are “the numbers that are only divisible by themselves and one.” If we were to learn only the extension of the term “prime number,” on the other hand, we would only have a list of the numbers that we know are prime.

It is clear that if we only have this definition by extension and we encounter a new, very large number— higher than the largest number on the list we’ve learned—we will have no criteria for knowing whether it’s prime. But if we have the formal definition by intension, we will, with the help of a calculator, be able to determine whether it is only divisible by one and itself and, therefore, prime.

We can’t productively critique the arguments of others if we don’t share their definitions of concepts.

When we are young, we learn about the world through definitions by extension during the course of our interactions with objects and other people. Our brain defines concepts by extension and then extracts the common features to produce a working definition.

But these definitions are subjective since they depend on our history of encounters with relevant examples. Thus, all of the concepts we have created do not match other people’s concepts precisely, despite being identically named. They depend on the particular experiences we have had.

Yet, towards the ages of 13 to 15, with mathematical and formal logic, it becomes possible to define concepts by intension and, therefore, to share objective meaning with others. Teenagers can enter a world of shared and precise meanings. This is a prerequisite for the application of precise and formal critical thinking. We can’t productively critique the arguments of others if we don’t share their definitions of concepts.

The formal approach for children aged 13 and up should, then be twofold: formalize the definition of the concepts used and formalize the logical deduction itself. This comes with practice and enhances both children’s capacity to communicate and their critical faculties.

Recognizing Faulty Reasoning

As has been discussed in previous sections, developing critical reasoning requires more than simply knowing how to reason formally and contextually. It is also necessary to learn how to recognize flaws in the reasoning of other people who may wish to convince us of their way of thinking, either for narcissistic reasons or to lead us to act to their own advantage.

Such flaws can occur on several levels:

Erroneous rules of logic, leading to false reasoning based on reliable hypotheses.

False hypotheses (starting points for reasoning): even if the reasoning is valid, the conclusion may be false. Certain politicians use this strategy very frequently.

Using a formal rule in a situation to which it does not apply. This often occurs in over-simplified mathematical modeling of complex material, for example when an essay in the humanities is interpreted using only the tools of formal logic.

These three types of flaws can be worked into family discussions, with the goal of training children to counter weak or manipulative lines of argument. School should not be too heavily relied upon to provide this kind of practice for your children. Already between the ages of 13 and 15, they are able to construct brilliant lines of reasoning, which will prevent them from being tricked by manipulative or intellectually limited people.

3. Individuation

What is individuation

Individuating and the stages of individuation are concepts developed by renowned analytical psychologist Carl Jung. Jung founded analytic psychology and the concepts of extraverted and introverted personalities, archetypes, and the collective unconscious were also developed by Jung along with the theory of individuation.

In adolescence, the individuation process heralds the initial stages that a child takes toward becoming a unique individual, something more than just your parents’ offspring, is a psychological necessity.

Part of differentiating yourself from the world around you is developing a self-image. It is the only way to avoid fading completely into your surroundings—and ending up in utter conformity, or worse.

Summary

Teenagers have a natural impulse to try to separate themselves from their parents and their backgrounds. A good critical thinking foundation can help ease the transition toward individuality and adulthood. Better reasoning can help teenagers cope with their emerging independence and avoid an unthinking rejection of their background.

Individuation adolescence

Individuation is indispensable to society. In order to sustain itself, society needs diversity. Cultures lacking the social norm of individuation are more fragile. They produce citizens who have identical self-images and behavioral patterns, whereas adapting to change requires diversity, creativity, evolution, and, therefore, critical thinking.

Only very rarely (or not at all) have individuals in these cultures of weak individuation experienced the feelings of crisis and malaise we associate with adolescence. The transition from childhood to adulthood unfolds instead according to so-called “rites of passage.”

Our civilization has undergone a long and profound evolution through philosophy, science, psychoanalysis, and politics, leading us to a social norm that rejects the idea that the individual in the family, the social group, or the nation, is like a mere cell in an organ. Indeed, everyone has the right and even the “duty” to be reborn by deviating from their origins.

This is an immense challenge because this act of individuation, this self-creation, arises at a moment when children are not yet able to achieve this “rebirth” autonomously, as they enter an unknown world without even knowing what it will be like. We call this period “adolescence” or even “kidulthood” when it lasts a long time—a growing phenomenon.

Experiencing society predominantly through school or family simultaneously generates pressure to conform and to individualize. It comes as no surprise that this causes some problems.

The desire to be free and independent generates psychological conflict.

What is the process of individuation

Children have not fully matured intellectually or cognitively when they are confronted with this contradiction. They are, therefore, unable to conceptualize it. This is why, in their behavior and attitudes, children can sometimes bear a closer resemblance to skittish animals than calm self-creators responsible for their own gradual reinvention.

Although unaware of it, children embark upon adolescence through “second-degree” conformity through culture, since adolescence is a societal construct rather than a psycho-behavioral component of puberty.

Paradoxically, children aged 13 to 15 or older may not experience teenage angst at all, thanks to their critical faculties. In fact, if they feel that their life is fulfilling and stable, they will be able to avoid getting sucked into an alternative world by other children their age. Their youth may pass without them having experienced teen crisis. Instead, they construct their identity reflectively and without drama.

This, of course, is not typical. The desire to be free and independent generates psychological conflict. The fear and the anxiety associated with this moment of struggle incites rationalizations, thoughts which retrospectively come to explain dissatisfaction, malaise, and rebellion. Every situation that is not comfortable or does not come off successfully, we tend to attribute to our external environment and other people. Consequently, if things are not going well for us—if we are not happy—we tend to blame it on an unjust world.

Parents of teenagers are very familiar with the result: sweeping criticism of everything teens encounter. To the teenager, everyone sucks: parents, teachers, politicians, journalists, and so on. This reaction can generate conflict, but, as is explained in the next section, it also presents a good opportunity for deepening critical faculties.

4. Teenage Negativity

It can be difficult to know how to react to teenagers’ negativity. On the one hand, their attitudes may seem too extreme and unsophisticated to take seriously. On the other, they can be exasperating and even hurtful when directed against the parents themselves. But parents should do their best to avoid being either dismissive or defensive.

The teenager’s emotional negativity is an extreme version of something we are all prone to indulge in from time to time, no matter how highly we may prize our calmness and understanding. Parents should remind themselves that this negativity is part of a bid to become a fully-fledged autonomous individual with an opinion deserving of recognition and respect.

Parents can help them reach this goal by taking their teens’ complaints seriously. This doesn’t mean telling them they’re right when they aren’t, but treating them as conversation partners worthy of engagement. Parents can ask their children to substantiate and defend their claims using argument and evidence; challenge their children when they fail to argue well; and compliment them when make good points.

Summary

The need to become an individual can often manifest itself in negative and unyielding attitudes. Though teenagers’ criticisms and complaints can be unsophisticated, parents should still engage with them. Critical reasoning can help make the process of becoming an individual less painful and more productive.

This can be a good opportunity for parents themselves to refresh their ability to put aside emotions and handle a topic fairly and dispassionately. By modeling these kinds of intellectual virtues parents make it more likely that their children will adopt them.

Arguing with teenagers can be fun, especially if they begin to experience the kind of satisfaction that comes out of reasoned debate over complicated issues..

Of course these arguments will not always go smoothly, but over time parents can help bring their children into the critical community. Arguing with teenagers can be fun, especially if they begin to experience the kind of satisfaction that comes out of reasoned debate over complicated issues.

The quest for individuality also manifests itself in a need to create or to win over a new group, a group that can become one’s ideal family. The phenomenon of teenage cliques or gangs—and even radical organizations—arises from this fact. Not being understood or accepted is stifling. We need an escape valve, and so, as social animals, we create or join a group that meets our needs.

5. Sense of Belonging in a Community

What it means to belong

Belonging means acceptance into a larger whole, society, community, or organization. It’s a fairly common experience that occurs at many levels of life from the familial unit, to work, to school, to the society as a whole.

From the age of 12 to 13, in order for children to be able to articulate their disagreements with the status quo, they must develop their critical reasoning skills. As adults, we must, again, engage with these critiques if they are well-founded. This shows children that rejecting their endeavors is not the automatic response. This makes them feel valued and capable of exercising autonomous thought which can, moreover, influence adults.

In this way, critical thinking also—perhaps unexpectedly—makes it easier for children to accept at least a part of the cultural heritage that is offered to or imposed on them by language, upbringing, and custom.

Summary

Although they may relentlessly criticize society, in so doing teenagers are really showing that they belong to it. Parents should help teenagers learn to articulate their dissatisfaction and develop a sense of belonging. . Critical thinking can help them reconcile their desire for independence with the value of tradition and belonging to society.

Allowing a teenager to convince others through argument and logical inference makes them feel more able to become an individual without breaking away from the group—a rebellion-free evolution. If they are allowed to articulate their dissent, they may even find school or home life less stifling than social life in a peer group where they are constantly pressured to conform. Encouraging this kind of critical thinking also protects them from negative influences (cults, crime, etc.), since their critical toolkit allows them to stay lucid when faced with wild, dangerous speech and behavior (alcohol, drugs, etc.).

From as early an age as possible, learning how to argue and reason critically using one’s capacities for inference allows for a balance in adolescence between individualization and an acceptance of heritage.

Indeed, the need to distinguish oneself and to proclaim one’s individuality is always met by membership in a group—now often with the help of social media. This need is only met if these groups are not as prescriptive and stifling as the society from which the child is trying to escape and if they do not cause harm.

Part of critical reasoning is the development of the capacity to question environmental, familial, and social norms and prescriptions. But this requires competence in a universal language made up of inferential logic and the art of arguing, which comes from the critiqued society. Critical reasoning itself thus serves as lasting proof that one remains a part of that society. In the very act of distinguishing themselves from the pack, teenagers show they belong.

Critical reasoning anchors children in reality, allowing them to achieve individuality in their own unique way. Parents can help by supporting their children’s projects and encouraging them to engage with the world around them.

Building a sense of belonging

Cultural heritage—including language, law, food, art, manners and customs, traditions, and scientific knowledge—represents an incredible resource that is at once imposed and offered. Teaching children critical thinking and reasoning means that they will not simply dismiss this priceless treasure in its entirety even though they will partially free themselves from it. Critical reasoning makes the process of individualization less violent and painful for both children and parents, thanks to the balance between the assimilation of culture and a healthy questioning of it.

In other words, critical reasoning—expressed through argumentative and logical know-how and rooted in self-esteem and love—anchors children in reality, allowing them to achieve individuality in their own unique way. Parents can help by supporting their children’s projects and encouraging them to engage with the world around them.

Cognitive faculties participate, in this way, in the psychological make-up of children. Critical reasoning has a twofold power: it is both integrator and liberator. It alerts us to the ways our culture forms us and helps us partly to overcome it. It is a fundamental pillar of our citizenship, on a national and global scale.

Benefits of sense of belonging

Critical reasoning serves as proof to children that they are listened to and that they are the primary drivers of their own destinies. Subsequently, they are predisposed to put their faith in the future and in others. They become psychologically and intellectually equipped to imagine a future with other people, in which they undertake communal projects and attain important goals.

6. Analyzing Sources

By the age of 13, young people likely already have significant experience navigating the internet. They have all made extensive use of a variety of websites in order to find answers to their questions or to help with papers and schoolwork.

The internet has democratized the transmission of information, allowing anyone and everyone to put forward their ideas, opinions, or hypotheses on multiple online platforms. People usually post things online in an affirmative style which presents any given statement, no matter how dubious or speculative, as a well-known fact.

People’s personal blogs, companies’ promotional lifestyle websites, and free encyclopedias all feature articles on complex subjects, almost always with content that has not been vetted by any experts, whose critical thinking skills and reasoning would be invaluable.

Summary

Teenagers need support to cope with and analyze disinformation and deception online. They should work on developing critical reading and browsing habits and learn to identify different kinds of deceptive reasoning. Families can practice analyzing false or misleading information together.

Debunking these types of conspiracy theories, with the help of parents and educators, can be a useful exercise for students.

In analyzing these and similar sources, we will arrive at one of five possible situations:

An author has good intentions but his or her reasoning is flawed. The author draws unsubstantiated conclusions from trustworthy information. For example, we have proof that certain particles came out of thin air and did not evolve from anything. Some wrongly conclude that this proves the existence of God, since only God could create something from nothing. This information is true, but the reasoning is false, and the conclusion therefore does not follow. The solution involves the relationship between energy and mass in the equation E = mc2. In empty space, even the smallest amount of heat can cause spontaneous conversions of pure energy into matter.

An author has good intentions and reasons well, but uses false information. Here, the author can come to false conclusions, even if he or she reasons impeccably. For example, one could conclude that the acceleration of an object, induced by gravitational force, is dependent on its mass because if one drops a rock and a feather from a balcony, the rock will hit the ground before the feather. Here, the problem lies with the initial information, which is erroneous because it does not take the role of air resistance into account. The observation on which the argument is based is thus incorrect in this case, as is the conclusion. In reality, in a vacuum, the feather and the rock would reach the ground at exactly the same time.

It could be that the hypotheses and baseline observations, as well as the arguments drawn from it, are all incorrect. A false conclusion is likely to result.

Authors could be giving out false information intentionally with the aim of selling a product; harming another individual, group, or country; spreading a rumor to make themselves feel important; or sadistically causing mental anguish to others for their own enjoyment.

An author intends to get a point across by using an argument which appears to comply with logical reasoning but which actually contains one or more inferential leaps, deliberately introduced in order to prove that the conclusion is objective because it stems from rigorous thinking. Sophistry and paralogisms arise from this sort of trickery.

It is very important to expose adolescents to these five possible kinds of lies or deception, as well as to reflect on how to identify them by analyzing authors’ arguments and questioning the hypotheses or observations at the root of their arguments and their likely intentions, given the message’s context. For example, in an advertising context, we can understand that car manufacturers might benefit from lying about the amount of pollution produced by the vehicle they sell.

7. The Critical Mind

What it means to belong

General knowledge is also a powerful tool for staying critical and skeptical in the face of this influx of information. It allows one to reconcile information and to check whether new data seems consistent with what they already know.

For example, if one were trying to evaluate arguments about how to address the recession caused by the 2008 global financial crisis, it would be useful to know the history of efforts to boost economic growth through government spending, especially those undertaken during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Citizens versed in this history will be far better equipped to evaluate and criticize the proposals put forward by politicians and economists in their own time.

Summary

Genuine critical thinking requires background knowledge. Parents should help their children acquire broad and deep knowledge so they have the confidence and ability to call sources into question and avoid an unreflective acceptance of authority.

Having general knowledge also means that one does not hold even the most reliable sources sacred, knowing that careful thought often undermines received wisdom.

For example, Einstein’s theory of general relativity called Newton’s law of universal gravitation into question, even though Newton’s law had apparently been confirmed by a wealth of experiments and observations. Einstein’s general knowledge and his independent way of thinking allowed him to postulate that gravity was not simply a force but a warping of space-time in the vicinity of stars. Since then, independent observational astronomical predictions have always supported the theory of general relativity.

Treating certain sources as sacred can be as dangerous as uncritically accepting everything that comes from the internet or elsewhere. The same phenomenon is involved when religious texts are interpreted as legitimizing violence or intolerance.

The interpretation—as well as the cultural, social, geographical, and historical contextualization—of a piece of information is indispensable to the formation of a critical mind. But critical thinking is difficult. It takes training, as well as background knowledge, to determine the reliability of a source, and this determination can never be definitive or certain.

These examples show that if we are responsible for educating adolescents on the verification of sources, we must be careful not to give permanent, definitive credit to any piece of information or knowledge, even if it comes from a seemingly very reliable source. Critical thinking, provided that it does not lead to permanent doubt or paranoia, is truly a way of life, facilitating progress and freedom.

8. Critical Thinking and Progress

A goal (or a project or “dream”) is the meeting of, on the one hand, an idea born out of a need or desire and, on the other, a method—an “algorithm” for bringing the idea into reality. But these two dimensions to every goal are, in fact, two sides of the same coin, two facets of creativity.

As we have seen, the spark for critical thinking comes from self-esteem and unconditional love. This energy is indispensable to living with both a sense of joy and, at the same time, a continual dissatisfaction with the status quo. Taking joy in life is necessary to prevent this dissatisfaction from degenerating into depression or other pathologies. This joy provides the energy needed to turn dissatisfaction into ideas and dreams of change.

But in order for an idea to turn into a project capable of changing the world, both a methodology and logical, communicative rigor are required. These allow a large number of people to understand a problem in the same terms and gear themselves toward the same objectives. Without these tools, efforts at problem-solving tend to devolve into emotionalism or factionalism.

Summary

Critical thinking can help children not only learn to analyze the world around them, but act to try to change it. Good critical thinking can foster productive interests, deeper engagement with social problems, and the attitudes of good citizenship. In this way critical thinking is vital to social progress.

Methodological rigor is rooted in critical reasoning.

An education in critical thinking and reasoning is the best way to ensure a child can access goal-oriented thinking. A goal, much like the kind of formal logic we can exercise from the ages of 13 to 15, transforms the possible into the tangible.

Goal-oriented thinking leads children in their adolescence to join or set up active groups or associations. Activity in such groups requires skills in both logic and communication, and it tends to support their further development. It pushes those undertaking such projects to strike a balance between asserting themselves and listening to others—between critiquing and taking what others say on board.

In this sense, critical thinking and the drive it inspires to undertake projects can be a kind of citizenship training. To rigorously and plainly critique a complex system (whether it be political, scientific, or philosophical, theological) is always to act as a citizen. It is beneficial to all.

In this way critical thinking not only enables students to reach their intellectual potential; it can also help them find purpose and, through purpose, happiness. And, ultimately, it can help foster progress and social cohesion through cooperative action.

Critical thinking not only enables students to reach their intellectual potential; it can also help them find purpose and, through purpose, happiness.

These links between critical thinking, undertaking projects, and citizenship should further encourage parents and educators to guide children toward this spirit of joyful dissatisfaction, as well as toward logical reasoning and the art of arguing.

If this mindset is acquired, teenagers won’t need pressure from above to take action as citizens or to participate in projects for social change that are bigger than themselves. There always lies the risk that when parents mandate this kind of participation as a kind of chore, children will reject it out of principle.

Instead of hoping their children will swallow whole what is offered them, parents should encourage them to seek the truth—to learn to reason and argue. Those around them, and society as a whole, will benefit from their skills, their independence, and their spirit.

Reboot Case Studies

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Case Study 1

The Concepts of Intension and Extension

Beginning at around 13, students can begin formalizing their reasoning using intensional definitions. These formal definitions, which are internal to concepts themselves, rather than drawn from experience, can open up new avenues for reasoning and lead to new kinds of arguments.

Consider the following scenario:

During a presidential election campaign, 14-year-old Lea defends a candidate who, in her eyes, is the only one worth voting for. She explains her candidate’s platform to her friends around the table at lunch in the school cafeteria and says how she wishes she already had the right to vote and that she begged her parents to vote on her behalf.

Lea’s arguments seem to have convinced her friends, but Anna, sitting at one end of the table, interjects: ″Who cares? As my parents say, all presidents are liars! I’m never going to vote.”

The other girls and boys present agree loudly. A surprised Lea tries to think of a comeback, but can’t think of what to say.

The bell rings. Everyone gets up to go back to class.

When she gets home after school, Lea tells her mother about the scene at lunch and asks her opinion: ″What would you have said to Anna?”

If you were Lea’s mother, how would you have replied? How can you use reason to respond to Anna’s argument, which seems to be an argument from authority?

There are two ways to determine whether all presidents are liars or not:

- Extensional method: Research the history of presidential elections, and compare the promises made by candidates to their actions after being elected. This method will allow you to determine whether all presidents over the course of history have lied. Perhaps they all have lied. But even in this case, Anna’s argument would be valid but only up to the present day, since one cannot predict the future and, therefore, what a new president will do. Perhaps Lea could then defend her favored candidate by arguing that, once elected, he or she will be different.

- Intensional method: Research political science and show that the electoral system and certain institutions pressure candidates to lie in order to get elected and that this is considered the “rules of the game.” If this can be demonstrated, it would be a valid pattern for the past and the future. In this hypothesis, Anna’s argument will be valid for the present and the future (so long as the same institutions remain in effect). Notice, however, that this method gives Lea an opportunity for more subtle reasoning. All presidents may end up making false promises or misleading the public on certain points, but we can distinguish between deliberate, malicious lies and those that arise from the pressures of the office. This would allow her to poke holes in Anna’s rationale for not voting, since certain candidates may still be more honest than others.

Case Study 2

Flawed Reasoning

Use these examples of flawed reasoning to introduce logical vocabulary and help your children identify flawed reasoning and how to identify flaws in an argument.. More definitions and basic concepts can be found here.

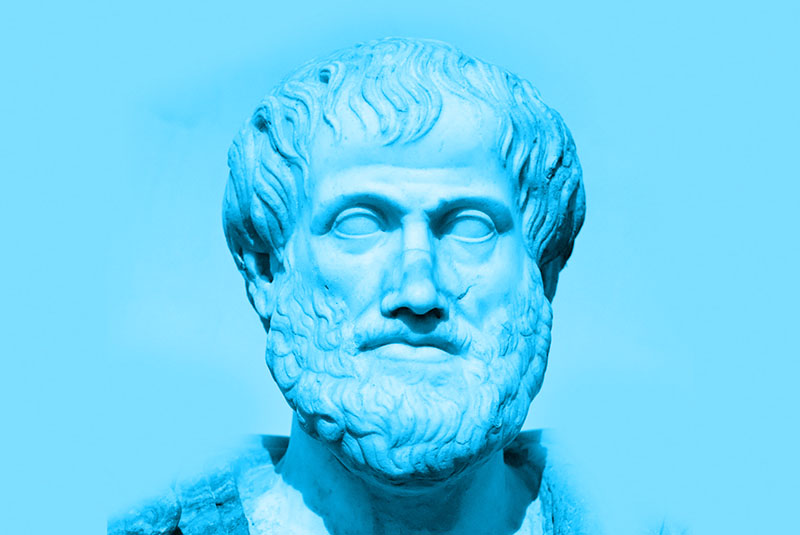

The examples are based on famous example of deductive reasoning attributed to Aristotle. In the exercises, Aristotle’s example is distorted in various ways, either using false information or faulty reasoning. Challenge your children to identify exactly why these arguments fail.

Here are some definitions of the terms used below:

Premises are the statements or information on which an argument is based (in these cases, the first two lines).

The conclusion (the third line in these examples) is the statement drawn from the premises.

When an argument is valid, that means its conclusion follows logically from its premises.

When an argument is sound, that means it is both valid and based on premises that are true, meaning its conclusion is also true.

These examples can help students to break up reasoning into logical steps, make the logical steps of an argument explicit to themselves, and identify where reasoning breaks down. Critical thinking must enable us to detect logical errors and to recognize whether they lead us to false conclusions. Notice, however, that flawed reasoning does not guarantee a false conclusion.

Aristotle’s Reasoning

“All human beings are mortal.

Socrates is a human being.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.”

The premises are true, the reasoning is valid, and the conclusion is, as a result, true.

Exercises

All human beings are women.

Socrates is a human being.

Therefore, Socrates is a woman.One of the premises is false, the reasoning is valid, but the conclusion is false.

Half the human race is female.

Socrates is a human being.

Therefore, Socrates is female.The premises are true, but the reasoning is invalid, and the conclusion is false.

Half the human race is male.

Socrates is a human being.

Therefore, Socrates is male.The premises are true, the reasoning is invalid, but the conclusion is true.

Case Study 3

Individuation and Belonging

Peer pressure emerges in adolescent social groups as children attempt to assert independence from their parents and build their own identity through involvement in peer groups. This can lead to a number of paradoxical problems as children are pulled between an emerging sense of self and a need to belong. Even as their children seek to separate, parents can offer them help and support in working through some of these conflicts.

Consider this scenario:

Twelve-year-old David has just entered sixth grade at a big middle school in the city. He is a bit lost and finds a group of boys his age to spend time with during class and at recess. They all get to know each other over the next few weeks.

At the end of October, one of the boys suggests that they draw a big skull and crossbones on their backpacks in permanent marker to show that they belong to the group. Within a few days, all of the boys in the group have proudly drawn a skull and crossbones onto the front of their backpacks— everyone, that is, except David. He really likes his backpack. He picked it out himself and his parents bought it for him for the new school year. Furthermore, he has never had an affinity for skeletons, and skulls and crossbones hold no special meaning for him.

When the group reunites in the playground one Friday morning, one of the boys goes over to David and threatens him, saying, “If you don’t draw a skull and crossbones on your backpack, you’re out of the group!” The other children back the mean kid up.

Over the weekend, David is faced with a dilemma. He can either keep his backpack the way he likes it, even if that means being excluded from the group, or draw a skull and crossbones on it to show that he belongs to the group.

On Sunday night, he decides to talk to his parents about the situation. If you were in their place, what advice would you give him?

At dinner, his father offers him some advice:

″David, you shouldn’t see this as a problem with only two solutions. Just tell your friends that you don’t like either option and that you have another idea.”

″That won’t work. They told me that it had to be one way or the other,” replies David.

″Well, you should at least give it a try,” suggests his mother. “Tell them that you really like being part of the group and that you like them as friends, but that you don’t want to ruin your new backpack by drawing on it. Tell them that, in a group, everyone should have their freedom and that you shouldn’t have to do the same thing as everyone else all the time. Ask them to let you stay in their group, which means a lot to you, without having to do something you don’t want to. That’s a third solution.”

In this situation, the group of boys want David to show he’s part of the group by adopting a common code. David is under pressure to comply and must make a decision. The easiest solution for David would be to succumb to peer pressure. He could also stand his ground and refuse, but this would probably cause him pain since he would have to deal with the group’s disapproval and possible exclusion.

The group does not tolerate non-conformity since it threatens its existence. Eventually, however, resisting peer pressure could play in David’s favor, as his show of independence could earn him the respect of the other group members and thereby bolster his self-esteem.

There is no ″right decision.” Everything depends on David’s level of self-esteem, which will determine his capacity to stand firm in the face of the consequences of his choices.

Case Study 4

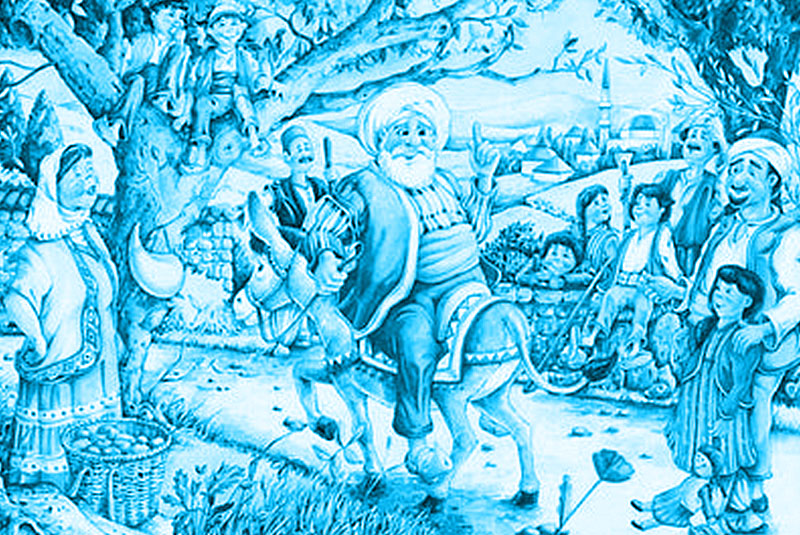

Nasreddin’s Sophisms

Nasreddin, a very famous figure in the Arab Muslim world, was the author of often absurd stories. Families enjoy reading his stories together and refuting his biased reasoning, which is designed to sharpen our critical thinking skills and ability to foil sophistry. Identifying the flaws in Nasreddin’s reasoning is a useful logic game and a good way to introduce logical concepts. Challenge your children to show where Nasreddin goes wrong, and come up with equivalent examples from current events or everyday life that involve the same flawed reasoning.

The Tigers

Very early one morning, Nasreddin was up sowing salt all around his house.

“What on earth are you doing with all that salt, Nasreddin?” asked his neighbor.

“I’m putting it around my house to ward off tigers.”

“But there aren’t any tigers here.”

“Well then, that’s proof that the salt worked!”

The Moon and the Sun

One day, Nasreddin was asked:

“Tell us, Nasreddin, which is more important: the sun or the moon?”

“The moon, of course,” he replied immediately.

“And why?”

“Because the moon appears at night, and that’s when we need light most.”

The Power of Age

Nasreddin arrived at a café one day, looking proud and happy.

“Hey, Nasreddin,” his friends called to him. “You look as if you’ve just found treasure.”

“Even better, even better,” he replied. “I am 70 and I have just discovered that I am still as strong as I was when I was 20.”

“And how did you discover that?”

“Simple! You see that huge rock in front of my house? Well, when I was 20, I couldn’t move it.

“So?”

“Today, I tried again and I still can’t move it, just like when I was 20.”

Case Study 5

Paralogisms

Paralogism Exercise #1

Spot the paralogisms in the following statements and explain why the reasoning is flawed.

″If smoking were bad for your health, it would be banned.

Smoking is not banned.

Therefore, smoking is not bad for your health.”

″If I am sick, I go see the doctor.

I am not going to see the doctor.

Therefore, I am not sick.”

″Intensive farming allows us to feed all human beings.

Organic farming is not intensive farming.

Therefore, organic farming will not allow us to feed all human beings.”

Paralogism Exercise #2

Three false dilemmas are presented below. Why are these apparent dilemmas not real dilemmas?

A close friend who is going to jump into a freezing lake on New Year’s Eve says, “A real friend wouldn’t let me do this alone.”

The night before election day, a candidate for office says, “It’s me or chaos.”

A slogan in an advertisement for Sneakie sports shoes reads, “Cool people wear Sneakies.”

Paralogism Exercise #3

Often biased or flawed reasoning uses false generalizations. How can we contradict the following statements?

Upon hearing that a politician is being investigated for tax fraud: “See? All politicians are corrupt.”

“Hypnosis works for giving up smoking. My brother managed to quit that way.”

“Social media is the best way to find love. Several of my friends met their partners that way.”

Paralogism Exercise #4

Beware of an “argument from authority,” especially those circulating online.

″Many scientists dispute the global warming phenomenon.” Who are these “scientists”? On which scientific studies have they based their opinions? Do they have personal, political, or economic connections with people or organizations that could benefit from challenging global warming? It is important to ask oneself all of these questions before accepting an argument.

Paralogism Exercise #5

Arguments based on numbers:

″This singer’s video already has 500,000 views online.” What does this say about the quality of their music?

″X93 – the latest phone, already owned by 2,000,000 people worldwide.” Does this mean that this device would suit my needs? Is this an indicator of its quality?

Paralogism Exercise #6

Arguments based on fear:

″You say that you’re against the death penalty, but murder will be much more common if we abolish it as a deterrent.”

Case Study 6

Fact-Checking

Several media companies offer fact-checking services. It is beneficial to consult them with teenagers and to pose questions about the ways in which media can distort the truth. These services can offer insight into the techniques various organizations and bad actors use to deceive audiences, as well as into the bias that can skew the information put out by various news organizations. Discussing these examples with your children get help raise awareness of the various ploys used to manipulate readers and viewers, and help them hone their analytical and critical skills.

Here are links to some trustworthy fact-checking sites:

Politifact | Snopes | FactCheck.org | Poynter Institute

Examining the false stories fact-checked by these organization can be a helpful exercise. Here is an example of a false story fact-checked by Snopes:

Understanding examples like these can give students insight into techniques fake news sites use to hook and deceive an audience. Here, for example, the violent image may grab viewers’ attention and cause them to let their critical guard now. Attaching the fake story to a genuine news item (Samsung’s smartphone recall) also makes readers more likely to believe and share the false story, since it appears like a development in an ongoing story.

Student’s can also learn from the fact-checkers’ analysis. Here, they track down the original photos to show how the fake site has repurposed them, and they dig into the website reputation and background.

Researchers Sam Wineburg and Sarah McGrew recommend teaching students to navigate the internet more like fact-checkers. Students, they write, tend to “read vertically, evaluating online articles as if they were printed news stories.” Fact checkers, on the other hand, “read laterally, jumping off the original page, opening up a new tab, Googling the name of the organization or its president.”

Fact-checkers, Wineburg and McGrew write, are also less inclined to trust a website’s own description of its mission. They look for outside evidence from multiple sources to confirm or refute the website’s claims. And they don’t get hooked by enticing language or images, instead reading through a whole page of search results or information before deciding reflectively what links to follow or where else to look.

Finding good information online—and steering clear of bad information—are skills that can be taught and learned. They are increasingly vital at a time where multiple interests are leveraging the internet to attempt to monopolize our attention and shape our beliefs.

Case Study 7

Verifying Sources

Several media companies offer fact-checking services. It is beneficial to consult them with teenagers and to pose questions about the ways in which media can distort the truth. These services can offer insight into the techniques various organizations and bad actors use to deceive audiences, as well as into the bias that can skew the information put out by various news organizations. Discussing these examples with your children get help raise awareness of the various ploys used to manipulate readers and viewers, and help them hone their analytical and critical skills.

Here are links to some trustworthy fact-checking sites:

Politifact | Snopes | FactCheck.org | Poynter Institute

Examining the false stories fact-checked by these organization can be a helpful exercise. Here is an example of a false story fact-checked by Snopes:

1. Questioning the Source

- What is the source? Is it reliable?

It is often possible to cast doubt on a source simply by looking at surface features. There are numerous fake news websites with unusual names or URLs (like, for example, worldnewsdailyreport.com) that should tip readers off to their unreliability. In addition, if a website looks poorly designed and managed, contains typos or formatting errors, this is also an important indicator that it is likely unreliable, if not intentionally false. Fake news also may also come under more plausible publication names, like, for example, the “Denver Guardian,” and with more convincing design. A simple internet search can usually bring up information from credible sources alerting the reader to the fraudulent nature of the source. Here is a list of unreliable news sources from Factcheck.org. With your child, practice determining the reliability of different kinds of information.

Who owns the source? Is the content sponsored?

When evaluating a source, it is also possible to do research into details about the source, such as who owns the source or who is funding the content or supporting it via advertising. It is often possible this way to identify potential biases or attempts to influence readers that may not be immediately clear at a first reading. Reliable sources may also sell space in their publications or websites to sponsors, who have obvious interests in what information is presented and the slant with which it is presented. See for example this “China Daily” paid post in the New York Times, which is placed on the Times website by Chinese state media. Exploring how and why information like this is presented can be a good learning experience. It is also useful to discuss how sponsored content is marked on this and other websites.

- Who is the author of the content? What are their credentials? What possible biases may they have?

In addition to asking questions about publications, it is important to know who has written a given article or op-ed, what their reasons for doing so may be, and what expertise they have in the given area. Doing so can help determine the reliability of the information offered, the possible slants or biases with which the information is presented, and any financial or other interest the writer may have in the matter discussed. Most reliable websites will offer at least some of an opinion writer’s background, but an internet search can often return more detailed information. It is also important to help students recognize that an editorial author’s potential biases do not necessarily render the content absolutely unreliable. Critical thinking should not lead to knee-jerk rejection of all potentially biased opinions. Rather, a fair-minded independent thinker takes potential bias into account in evaluating content, weighing it along with other factors, like the strength of the argument and the evidence put forward.

2. Questioning the Content

- What type of content is being offered? What is the issue under discussion?

Before we embark on an analysis of the content of a given source, it is important to identify what type of content is being offered. The way we approach analyzing an advertisement will be very different from the way we analyze a news story or an opinion piece. It’s also important that students be able to identify when a particular source is purposefully blurring the lines between categories. For example, so-called “advertorials” can disguise advertising or promotion in the guise of opinion pieces or feature articles. News stories may likewise present information in a particular misleading or biased manner, trying to persuade the reader of something, but without making it clear that they are actually offering an opinion, not simply news.

- What sources are drawn on for the information or argument given? Are they reliable?

Even when we are satisfied that a source we are reading is generally reliable, it is worthwhile to pay attention to its own sources of information. If a particular piece of content cites facts without providing sources there is good reason to question the information. Moreover, students should get in the habit of following links and citations to verify that the secondary information comes from a reliable source and that the original content is characterizing it accurately.

- What are the main arguments being offered? Are they strong and sound? Are they consistent with each other?

Media sources use a variety of means to try to convince the audience of a particular point or point of view. It is important to train ourselves to be conscious of what these means are and whether they are valid. If an article or video simply relies on emotional reactions or strong images to prove its point, without trying to put forward an argument, we should be skeptical. On the other hand, if there is an argument presented, we should begin training children to break it down and analyze it. Parents and their children can practice breaking down the argument into premises and conclusions, evaluating whether the evidence for the premises is strong and the conclusions follow rationally from them.

- How might one argue against the position put forward?

Another important exercise to carry out, even if you generally agree with a position put forward, is to ask how it might be opposed. This can help identify weak points in the argument and show where evidence, even if it’s reliable, may not fully support the point of view being put forward. To this end, it can be helpful to research articles with opposing points of view, but which rely on the same set of facts. Discuss the merits of each article and how you would argue for and against each of them.

Quiz

Ages 13+

Complete the quiz to review important points in the guide.