Fact checkers face the difficulty of getting readers to retain key bits of information from fact checks, and ultimately whether a claim is true or false. Online multiple-choice quizzes present an opportunity for encouraging users taking fact checks to engage with content and to learn more from the misinformation debunk. Previous work from The Center for Media Engagement finds that quizzes can improve time spent reading news or one’s political knowledge.

In this project, we investigated interactive quizzes as a tool that fact checkers might be able to use to improve readers’ memory for key details from a fact check, as well as their beliefs about the accuracy of the fact-checked claim. In our studies, exposure to fact checks improved individuals’ ability to accurately identify claims as true or false. We also found that multiple-choice quizzes improved peoples’ memory for the key details from the fact check. However, improving readers’ memory did not change whether they thought the claim from the fact check was true or false.

We conducted three online experiments to measure how the presence of a multiple-choice quiz, either before or after a fact check, influences people’s memory for key pieces of information from the fact check and their ability to identify claims as true or false. We concluded that quizzes are a useful tool for fact checkers to encourage lasting memory for details from their fact checks. However, quizzes do not improve readers’ judgments of the accuracy of the fact-checked claim.

Our research offers cautionary evidence for fact checkers or news organizations who might spend valuable time and resources implementing multiple-choice quizzes. While quizzes do not appear to change a person’s beliefs, they may be useful for fact checkers to assess the effectiveness of their articles, or whether readers are retaining the most significant pieces of information that serve to debunk a claim. Additional research is needed to see if these long-term gains in knowledge aid in helping audiences reach more accurate conclusions. Read on for more details about our three experiments.

Can Quizzing Before or After Fact Checks Improve Memory and Accuracy?

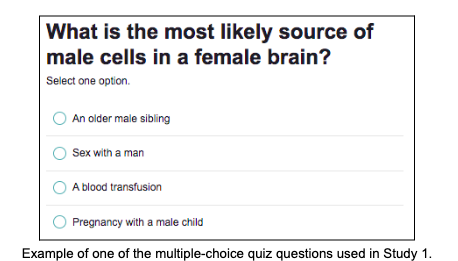

In our first study, we showed participants one of two articles that fact-checked a piece of health misinformation. We randomly varied whether participants saw a quiz before the fact check, a quiz after the fact check, or a fact check without a quiz. Participants who took the quizzes received feedback on the correct answer after answering each multiple-choice question. Immediately or one week later, we asked open-ended questions to measure how well people remembered key information from the fact check and asked participants to rate the accuracy of the false claim.

The results from this experiment produced three key takeaways:

- Multiple-choice quizzes do not decrease readers’ accuracy rating for the false claim.

- Multiple-choice quizzes (before or after the article) help readers recall specific details from a fact check.

- Even a week later, individuals quizzed before or after reading a fact-check, were more likely to recall those details.

Can Quizzing People on the Debunked Claim Itself Improve Memory and Accuracy?

In our second study, we used the same health misinformation as in Study 1. We randomly varied whether participants read either a fact check by itself or a fact check followed by two multiple-choice quiz questions. In Study 2, we tailored the quiz questions to be more directly related to the false claim. We targeted the key information that made the claim incorrect. The results were the same as in Study 1. Quizzes again improved people’s memory for the information in the article, but they did not change their belief in the false claim.

Can Quizzing People on True or False Claims Improve Memory and Accuracy?

In Study 3, we included both true and false claims for participants to read and evaluate. We also used political misinformation to extend our findings beyond health misinformation. Participants were shown a series of four fact checks and were quizzed after two of the articles. One week later, participants answered questions about the fact check and rated the accuracy of the fact-checked claims and four new claims.

We found that the fact-checks were effective – people were more accurate at rating the truth of claims when they read the relevant article. Taking the multiple-choice test also improved respondents’ memory for the information in the article a week later. But, again, the quizzes did not alter people’s beliefs about the accuracy of true or false claims.

What Our Research Means for Fact Checkers

Our research produced several significant findings for fact-checking organizations or newsrooms implementing fact checks.

First, multiple-choice quizzes present a useful tool for fact checkers aiming to improve people’s memory of key details within a fact check. This finding seems especially useful for fact checkers aiming to debunk complex topics like health or politics. Across three studies, we found that people’s memory for complex details from fact checks, such as, “what is the blood-brain barrier” improved after receiving a quiz along with the debunked claim (even one week later). We recommend that journalists consider implementing quizzes as a means of helping the public digest and recall new information.

Second, multiple-choice quizzes are not a panacea for misinformation. Despite finding that quizzes aid in memory, we did not find that multiple-choice quizzes are effective at changing people’s beliefs about whether a claim is true or false. Understandably, changing a person’s mind is a tall order that cannot be solved with a quiz alone. Based on this finding, we still encourage fact-checking organizations and newsrooms to implement multiple-choice quizzes but acknowledge that they have limitations. We also want to emphasize that while the quizzes did not add additional benefits to the fact-checking articles, the articles themselves were beneficial. Readers’ beliefs were more accurate after reading the articles, suggesting that fact-checking articles can be a useful tool for combating misinformation.

Thank you to Democracy Fund, the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Reboot Foundation for funding this research.

By Lisa Fazio, an Associate Professor of Psychology at Vanderbilt University; Jessica Collier, an Assistant Professor of Communication at Mississippi State University; and Raunak Pillai, a doctoral student in psychology at Vanderbilt University.

The research outlined in this article was partially funded by the Reboot Foundation.